|

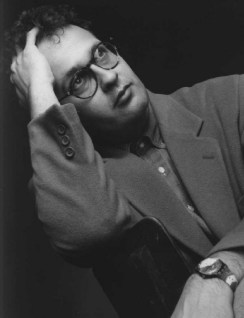

Andrej Blatnik

[links]

Andrej Blatnik (1963, Ljubljana, Slovenija), writer, editor. He has written

two novels, Plamenice in solze (Torches and Tears, 1987) and Tao ljubezni

(Closer to Love, 1996), two books of essays and four collections of short

stories, including Menjave kož (Skinswaps, 1990) and Zakon želje (Law

of Desire, 2000). His short stories and essays have appeared in numerous

literary magazines around the globe, as well as in various anthologies.

The translation of his book Menjave kož was published in Spanish (Cambios

de piel, Libertarias/Prodhufi, Madrid 1997), Croatian (Promjene koža,

Durieux, Zagreb 1998) and English (Skinswaps, Northwestern University

Press, Evanston 1998), and is forthcoming in German. Tao ljubezni was

published in Croatian (Tao ljubavi, Meandar, Zagreb 1998) and Slovakian

(Tao lásky, F.R. & G., Bratislava 2000). Law of Desire is scheduled

for publication in German and Croatian. Andrej Blatnik was a participant

of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, Iowa City,

USA, in 1993. He has received various fellowships, including Fulbright,

the Austrian KulturKontakt fellowship, and a grant from the Japanese government.

He enjoys travelling, always on a shoestring.

|

A THIN RED LINE

When Hunter arrived in Ayemhir the village was shrouded in twilight.

The children had begun to screech the moment they spotted the unknown figure,

but when they could make out his white, almost translucent skin, they became

embarrassed. They huddled in a group and covered their genitals with their hands.

Mzungu, mzungu, they whispered to one another. Hunter nodded and

waited.

Next came the headman. Hunter handed him the bag of salt and told

him the name of the sender. The headman scowled, and Hunter felt that the young

man he'd met on one of his drinking tours of the waterfront dives and who'd

told him to go visit his village, wasn't so much in the villagers' good books

as he'd bragged over his drink. But it was too late now for Hunter to change

his mind. The bus only came to these parts once a week, when there was regular

bus service at all.

The headman addressed him in his guttural speech, of which Hunter

could not make out a syllable. The old man repeated his jabber two more times,

then gave up and summoned somebody who spoke a little Swahili. Hunter tried

to explain in the best Swahili he could muster that he was not really fluent

in that either and then asked for the use of the empty hut, the kind that is

available to visitors in every village. The headman nodded and kept nodding,

then stared at Hunter for a long time, apparently pondering something. Hunter

could feel the rivulets of sweat trickling down his back. It was such a long

walk back to town.

Suddenly the headman seized Hunter's worn backpack and weighed

it in his hand. Instinctively, Hunter's hand shot out. Ever since the mugging

he'd mentally practiced this gesture, every time he was scraping the bottom

of his tin plate at some road-side eating stall or entering notes in his travel

journal: a passing thief tries to snatch his backpack but he's quicker, he grabs

his bag, maybe even the thief's hand, and everything's clear, it's all resolved.

There is no doubt. But the situation never occurred, all his alertness had proven

pointless, no-one else craved his traveler's possessions. And now he'd reacted

at a wrong moment.

The headman gave him a questioning look, and Hunter thought he

had caused his own undoing. How could they take into their village someone who

didn't trust them? Out here in the open feelings must be mutual, as equally

portioned as possible. If he does not trust them, how can they trust him?

He tried to mitigate his mistake, pretending on an impulse to

need something urgently, but what could be so urgently required by a man who

had possibly just been granted a roof over his head, that is, the only thing

available in the village? His best option, he decided, was to pretend he wanted

to give the headman something else in addition to the salt. So he rummaged through

his backpack, but after the long months of his going walkabout there wasn't

much left. His fingers finally encountered a smooth surface that he knew: His

little shaving mirror, from the time when he still bothered to shave. He wouldn't

be needing it now, he realized. He handed it to the headman.

The headman accepted it cautiously and diffidently looked at his

own reflection in the small rectangle. Then he raptly began to study his image

close up to his eyes and then at a distance. He seemed to find the face in the

mirror familiar, but not familiar enough to address.

He did address Hunter, though. Actually, he addressed the mirror,

and the man who spoke some Swahili nodded and said something in Swahili. Hunter

did not understand a word except for mzungu, foreigner. Helplessly he

shrugged, and equally helplessly the translator shrugged. The headman nodded

and uttered a single word: "Mary."

The children shrieked and rushed off toward the edge of the village.

The translator shook hands with Hunter, squatted before the headman and began

to retreat backwards. The headman motioned to Hunter to sit down. Hunter looked

at the ground, at the exact spot the headman had indicated, and automatically

wiped off the dust. In vain: There was only more dust underneath.

Then they waited in silence, until a woman approached, squatted

in front of the headman, and said to Hunter: "Welcome."

Hunter thought he had gone out of his mind. Ever since he had

drunk water from the village well in Ga-mendi he hadn't felt exactly clear-headed,

but rather as if his eyesight and hearing might have been affected. In any case,

this was the first English he'd heard since he spoke to the two Frenchmen who

were driving the stolen car across the Sahara and who had taken his money-belt

and his papers. They'd had a simple strategy: A knife blade against the throat.

All the boot camp training Cherin had made him attend was of no avail when he

came into contact with the sharp, cold metal. He did not feel excessively humiliated,

though; after all, he had spent most of the time during training pondering how

he was not the right guy for the job.

"Do you speak English?" he asked. The woman nodded.

"I do. Just call me Mary. My real name's different,

but I'll be Mary to you."

"How come? Where did you learn English?"

The woman smiled at his astonishment.

"I went to university in the United States. Washington

D.C. I never graduated, though. I stayed on for a while and worked in an African

restaurant, and then I came back."

"Why did you come back?" Hunter realized the insolence

of his question the moment he uttered it. If he'd come to this village, why

shouldn't anyone else? And in particular someone who'd departed from here sometime

before?

"If you can't change the fate of the majority, you

must share it," said the woman and looked at the ground.

The sentence had an oddly familiar ring to Hunter. It sounded

vaguely similar to what Cherin might say at a cell meeting when he ran out of

arguments in favor of suicide missions. Cherin incessantly kept sending him

the same questions by e-mail: Why did you run away? Why did you desert us? Hunter

never answered; where would that get him if he replied to the people he was

actually running away from, but if he had to decide on a single answer, it would

probably be: Because of stale rhetoric. That would cut Cherin to the quick.

The headman touched Hunter's hand and began to speak. He spoke

for a long time, and the young woman translated it all in a single sentence:

"He's glad you have come to our village."

Hunter took a deep breath. Finally the moment had come, the moment

he had been musing about all this time ever since he had decided to leave everything

behind and travel as far away as possible. He suddenly felt it was of utmost

importance how he formulated his question. Then it dawned on him that all his

caution was immaterial: He was totally at the mercy of the translator, who could

twist his words around any way she chose.

"I've come in search of the Nameless One," he

said. And hoped that she would understand him, that she would find the right

name in their unearthly language for the Nameless One, that the headman would

nod, that he would finally find what he has been seeking.

The woman did her translating. The headman scowled and gave her

a piercing look. The woman repeated her patter one more time, and now the headman

nodded at every word.

"The Nameless One," he enunciated, in English

that sounded no worse than Hunter's. And he continued in his own language.

"He says it's an honor to meet the Nameless One,"

explained the woman. "He says it's a great privilege to have the Nameless

One in his village."

Hunter felt the temperature rising with every word. The earth,

or not even earth, just pounded dust under his legs, emanated heat in waves.

"Well," he said, "well -" He knew what

he wanted to say, he wanted to ask: Who is he? What is the Nameless One like?

When is he coming? Can I see him? Can somebody introduce me? A thing like this

can and must only happen here, flashed through his mind, only here, in this

hole in the back of beyond, where else if not here where things haven't changed

their names hundreds of times, does this village have a name at all, it does,

but I can't recall it this minute, nobody knows it, not even on the bus where

they looked at me strangely when I shouted for them to stop, to pull over for

Christ's sake, and then I walked for a long, long time, I walked until my mouth

was all dry and it's still dry, so dry that right now I can't say a word -

The woman waited. To Hunter it seemed as though he could discern

scars on her ankles, the kind that leg irons would leave, but he could not be

absolutely sure.

The headman said something and the woman translated it immediately.

"You've finally arrived in our village."

Hunter did not understand.

"Were you expecting me?" he asked, surprised that

his voice found its way through the stuffy heat, and they both nodded simultaneously.

"Why were you expecting me?"

"We need you," said Mary.

Wrong, thought Hunter, wrong again. Like so many before. Like

too many times before. Far too many times for him to believe in coincidence

any more.

"If you need money -" he felt about his pockets,

but what he knew already could not be changed: He only had a few fifty-dollar

coins left.

The headman shook his head and Mary translated his motion into

English without hesitation.

"We don't need money," she said. "You're

here to give us something else, something that will be truly helpful."

Resigned, Hunter nodded. Cherin always said we had to get to the

point where money wasn't the most important thing in the world, and I've arrived

there, Hunter thought sarcastically. He waited to hear what the something was.

"Rain," Mary expounded.

"Rain?" Hunter glanced at the ground and then

at the sky. Both dry matters looked equally unreal to him, equally unchangeable,

eternal.

"Rain," started Hunter slowly, pondering the right

words, "does not depend on me." Nothing depends on me, he reminded

himself. But he did not say it.

The headman murmured something.

"The juice of life comes from the belly of creation,"

translated Mary. It sounded somehow solemn, somehow elevated, as though Cherin

was about to give the signal and they would burst into song.

"I don't understand," said Hunter.

"There's only one way out of a drought. Only one solution."

Hunter waited. Mary looked at him and he felt as though he could

read in her look more than just the search for the right words to translate.

That she was sizing him up, weighing him, as though she were picking him out

of a brood of similar specimens and fretting whether she'd made the right choice.

"After a long drought, it is customary for the headman

to sacrifice himself in a special ceremony."

"In a special ceremony?"

"He slits his belly and soaks the earth with his juice."

Blood-soaked earth. That's a sight Cherin would thoroughly enjoy,

thought Hunter. He should be here now - instead of me, he wished.

"I can see why he's putting it off," he said.

"No, you don't see," said Mary softly. "Not

yet."

Hunter looked at her questioningly.

"Our lore has it that sometimes a foreigner comes.

Who's got more juice. So that after his sacrifice it rains longer."

Hunter's head spun. In his mouth he could feel matter throbbing,

he felt his tissues fighting for liquid, and he licked his lips.

"You're making it up," he tried to reason. "You're

trying to scare me."

Mary shook her head.

"It's common knowledge. Everyone in the village knows

it. That's why they're so happy you came."

"Happy?" Hunter could not see anyone. Just the

woman and the headman. The children no longer dared come near.

"Happy," she confirmed. "There's going to

be plenty of rain."

Wrong. Wrong again, as so often before, thought Hunter.

"I have no intention of slicing open my stomach,"

he said. He tried hard to smile, but Mary's glare told him he had not quite

succeeded.

"You don't have a choice," she said, surprised.

"You don't have to share the fate of the majority. Because you can change

it. You don't have to die of thirst. Because -"

Because I can die of losing my own juices, thought Hunter.

"Do you believe in this sort of thing? You went to

university -"

"Yes, I do. I studied anthropology," said Mary.

Hunter nodded and suddenly felt tired, very tired. It occurred

to him that he hadn't checked his e-mail in a long time. That for a long time

he hadn't kept up with what was going on in the world. Cherin might have been

tracked down and shot dead in the meantime. Hunter could be the only one of

the cell still being searched for. Perhaps even they had stopped looking. The

only one who never gave up was Cherin. The others were not so tough. Cherin

told them they were bored children, that they were there just for fun, for the

hell of it. Because they'd thought it would be fun to shoot cops and throw bombs

and so they joined the cell. And Cherin told them over and over that the old

had to be demolished before the new could be established, and so they demolished.

For others, Cherin would say. We're not doing this for ourselves. For others.

Everything was for others. Cherin was a believer. And if he was gone -

Mary touched his hand.

"Come with me," she said.

Hunter hesitated. He felt it was all a bizarre misunderstanding,

that he only had to find the right word which would clear everything up, but

he couldn't think of anything, anything at all except the face of the child

he could never forget, and the woman's hand, the hand of that woman who was

everywhere with him, eternally reaching out to grasp the door handle -

"Where?" he said.

"Not far. You've come to the right place already,"

said Mary, "and we're almost ready."

Hunter thought of the plane ticket he'd carried around in his

shoe since the encounter with the Frenchmen; they'd graciously let him keep

it and advised him to use it as soon as possible, seeing as he was not cut out

for these rough parts. He'd been telling himself all the time that he could

not use it, that it was a useless piece of some useless stuff from a useless

world he no longer belonged to. Perhaps he had been wrong all along, but now

this would be true forever.

The man who suddenly materialized by the headman's side, holding

a brightly colored spear in his hand, nodded at Hunter amicably. Other warriors

came closer, and when Hunter did not move, they started jostling around him.

Every last one of them patted his shoulder and grinned widely.

"Our man," said one of them in Swahili and they

all nodded.

What Cherin wouldn't give to be in my shoes, to bond with the

simple folk so easily, thought Hunter and he had to start laughing. The guards

were elated by his mirth. They dropped to their knees in front of him and rolled

around in the dust. He heard drumbeats accelerating somewhere, and guttural

cries syncopating the rhythm, and approaching.

You're always making up your mind first, and then having second

thoughts, Cherin wrote to him. In a tight spot you run off with your tail between

your legs. You get lost, like a dog without a master. Like that time in front

of the embassy. All you had to do was cross the threshold and the mission would've

been accomplished. But you chickened out, you dropped the bag and ran. And then

that poor woman who came begging for a visa got blown up. And her child. And

the cell got a bad name. Killers of women and children, instead of exterminators

of the class enemy. There's a fine line between an unnecessary, pathetic, pitiful

death and a world-changing death. And you don't know how to cross that line.

The line, thought Hunter. To draw the line. In some languages

this means to set a limit, in others, to escape. Who knows what it means here.

The headman stood in front of him. He drew a knife from his belt

and proffered it, holding it by the blade. When the handle settled into Hunter's

palm, he realized with sudden clarity that all those men in illegal joints in

the port who'd told him that the Nameless One could be found in Ayemhir had

not been spinning a yarn; He was here alright, waiting. For Hunter.

The headman spread his arms. Hunter knew there was no other way.

He nodded and the headman nodded back at him. Hunter could read contentment

in the headman's face, happiness that this performer of sacrifice from the far-away

white world who was about to save the desert from drought had come to his village

and none other.

He took the knife, poised it against his abdomen, leaned

on it and cut. At first he could only see a thin red line. On his cheeks he

felt the first drops of rain.

Translated by Tamara Soban

THE DAY OF INDEPENDENCE

This is the story Papa will tell me, Papa, who'll know for a long

time to come how it was in the old days before you and me, in a time when you

could not accept a candy from a stranger in the street because it was poisoned

for sure, in the days when only strangers in the street had candies which you

could not accept if you wanted to stay alive, this is a story from the end of

that time and you have to hear it too, listen to it so that you can pass it

on to your children when the time comes. That's why I'm confiding it to you,

and we'll speak guardedly, sotto voce, choosing our words with care, as befits

those days of old, and we'll glance over our shoulders in case there's somebody

there, eavesdropping on what is none of their business.

He was there, Papa will boast, he was right there in the first

lines, up front, and the cork which popped uncontrolled from one of the numerous

bottles of champagne hit none other than him as he pushed his way to the platform,

stretching his hand holding a hard-won glass up to the scene, and the cork printed

a blackish bruise above his eye. As accidents never come alone, in surprise

he let go his frantic hold on the glass, which shattered on the ground, and

Papa, stumbling, fell on his hand and then, as soon as the people drew back

enough for him to pick himself up, he saw the crisscross of blood on his palm.

There were a few screams, nobody had expected blood, not on a

day they had been anticipating for so many years, generation after generation,

lifetime after lifetime, they all knew it was possible though nobody had expected

it to actually happen, but it happened, things like that do happen, it's alright

though, no harm done, everybody around him said, so that in the end Papa said

it too, what else could he do, it's alright, he said, and people laughed, patting

his shoulders, it's okay, it's alright, they called out all around, while his

palm dripped blood and hurt, it's alright, he said through clenched teeth, he

kept repeating it, and then he accepted the proffered glass of brandy and downed

it in one gulp, as fast as possible, and it really began to seem that it had

to be alright since everybody said so, himself included, that there could be

no harm, although his palm smarted strangely.

With the second glass it became crystalline clear to him that

everything was indeed alright, really and truly, if there had been something

that was not alright, that had been before, but no longer now and never again,

so he did not resist much when that girl started kissing him, it was rather

acceptable, there was plenty of kissing going on all around, it was a special

time like never before and possibly never again, and it's hard to hold back

if everyone else is kissing, in particular with a girl who does not even try

to hold you back, but quite to the contrary lays her hand on your bruise so

often that the pain disappears and is replaced by another feeling, pleasant

and unknown. And that's why Papa did not resist when this girl whispered to

him that it was really too crowded here and that also here, in the old part

of town - oh, not just a town anymore, as of tonight the capital - there were

plenty of hidden corners which have been there since always, waiting since always

for couples like them. And that's why Papa followed her, that's why he let her

take him by the hand and lead him into one of those dark hallways whose reason

for being might be that in them people can let out or shoot up fluids, into

one of those hallways whose murky darkness screens out unwanted stares, and

you know what happened in that hallway, things like that happen to everyone,

or nearly everyone, in particular on days like that which had never happened

before and will never happen again.

He doesn't remember much, Papa will tell me, he doesn't recall

exactly what happened to him in that hallway, it was over so fast, faster than

he expected or hoped, but it felt nice, pleasant, it felt the way it should

on a special day, the kind of day one experiences for the first time, if they

do at all, that is, because it seems, Papa will go on, that there are also people

to whom these things never happen, but such people, Papa will add, don't really

know what they're missing, and so possibly they don't feel so bad about it as

they would if they did.

He does recall, though, Papa will also tell me, that when they

picked up their things and went back outside, under the independent sky, a woman

spoke to them, a woman dragging behind her several flattened cardboard boxes

tied together with a piece of string. Excuse me, do you two live in a box, she

asked, and Papa recalls shaking his head, he recalls looking in his woman's

eyes and seeing them fill with horror. Then give me some change, the cardboard

woman rejoined, and Papa recalls reaching into his pocket without hesitation,

expecting to find something there, but there was nothing, he had left everything

at the stands where champagne was served, nothing was free, not even on a day

like this, is anything ever free if nothing is free on a day like this, he recalls

reaching into his pocket and not finding anything there, and his woman took

him by the hand, no, no, she said, although he himself had also felt that no,

that wouldn't do, even though he might have wished that it could have. And he

recalls, Papa will finally tell me, how they went on together, he and this woman

from the hallway, his woman for the night, with whom he was to become a couple,

but not right away, not that night, oh, no, quite some time would go by, first

they would circle around each other, pondering whether they should or should

not, but then they found out about me and finally owed up that they were a couple,

Papa will finish, and how they went on and how the cardboard woman followed

them with her eyes for a long time, before she began arranging her cardboard

boxes in the hallway, that hallway they had just vacated.

This is the story Papa will tell me when I ask how I came into

this world, and he'll tell it to me softly, as though embarrassed about things

being the way they were, about his palm bleeding and about not finding anything

when he reached in his pocket. And I won't understand why he's embarrassed,

just as you don't understand why I'm embarrassed when I tell you this story,

and just as your children won't understand you when the time comes for them

to know about it.

But that is still far in the future, let's leave that for you,

to deal with when the time comes. Another story is about to happen, I can't

hold back any longer, my day is coming. I'm about to come into the world, I'll

delight in the gust of air which will penetrate my body, it will be all different

than it is inside here, it will be all unknown and large, dissimilar, that's

good, it can't be anything but good, and I'll scream for joy. The woman I'll

later, much later learn to call Mom will be there, gasping somewhere in the

background, what is this?, I'll ask myself, what's going on? why doesn't this

voice shut up? And Papa will lean close to me, he'll touch me, and I'll feel

for the first time the raspy, cold skin which will be close to me so many times

in the future, it will be an odd feeling, not unpleasant, just odd, when before

that everything around me pulsated and gurgled, and now suddenly this. And he'll

say something to me, but I won't understand what he's saying.

Papa. Papa. This is the way it's going to be, Papa. You'll come

into my life, you'll be in it, and I'll devote a lot of time and effort to figuring

out your stories. Stories from the old days without me, from a time when you

could not accept a candy from a stranger in the street because it was poisoned

for sure.

Translated by Tamara Soban