Eda Èufer: REFLECTIONS ON M 3

The 1990's should be remembered as a truly exceptional time interval and it will be very interesting to observe if the memory of these years will lose its strength just as fast and ruthless as the no less exiting and intensive 80’s. We entered the past decade with a feeling of emptiness and disorientation, a feeling which was immediately compensated with the incredible speed and euphoria with which completely new and unexpected social processes started forming. Today we rarely remember that in the mid 80's nobody could predict the end of socialism in the East with certainty. On the other hand, Western Europe, which was at the end of the 80’s already very far with its preparation for unification, could by no means be prepared, nor for the collapse of socialism, nor for the wild dynamics and political complexity, which was released with the ‘new economy’ of globalism. Maybe the phenomenon of the so called ‘new pragmatism’, which is attributed to the moral image of the 90’s art and which many of us accept with certain restrictions, is a side effect of the all round improvisation and experimenting with which the processes of adjusting to the new political, economic and technological conditions were marked.

Some critics of the ‘new conditions’ (see texts by Peter Lunenfeld in the ‘nettime’ and ‘rhizome’ archives or the text published on the ‘iniva><blast’ list, 21st March 2000) are of the opinion that after the year 1968, 1989 is the new marker point for distinguishing the great paradigmatic turn in which we can currently still be found. In a parable this moment can be shown as a state in which the head still thinks in the old fashioned way, while the feet are already deep in the mud of the rules of the reorganised field. Even though we prefer to reproach this to others (the West, East, America, our competition, etc.), we are all in one way or another confronted with the challenge, a challenge in which it becomes harder and harder for us to adjust our actions with our desires, beliefs or ethical parameters of cultural and art programmes which we are performing. On one side, the only stable ethical basis for critical reflections on contemporary art and cultural productions that we have are those, that have developed from the ‘pre’ and ‘post’ 1968 theoretical and critical thought and are oriented to the ‘left’ i.e. are ‘anti-marketing’, while on the other side it is hard for us today to think of an alternative to capitalism. That is why the issue of the market and its forces are becoming the central issues of the so-called ‘post 89’ theory of aesthetic production. The ideologists of the ‘new conditions’ for planning contemporary and future aesthetic strategies propose ‘taking into account, but not unconditional acceptance’ of market laws. The difference between ‘taking into account’ but not ‘unconditionally accepting’ of course does not offer concrete instructions or rules of ethical behaviour and in this difficult vagueness of the generally adopted ‘right’ direction of operation, as opposed to the ‘not permitted’, ‘ethically dubious’ direction of operation, a great complexity, confusion and aggression of relations are hidden. All of these are a part of our existence within the frames of contemporary aesthetic production.

Manifesta, the European biennial of contemporary art, was launched in 1996, as a travelling, horizontally organised institution of the ‘new’ Europe, which should discuss those events that so unexpectedly emerged in the 1990’s Europe. In order to understand the political and cultural vastness of this event we can compare it to two similar events, the Venice Biennale and the Kassel Documenta. The Venice Biennale was established at the end of the 19th Century and marks and celebrates the moment when the formed national states started to form a transparent system of international economic and cultural exchange. The German Documenta, established after World War II. by all means stands in a defined, more or less obvious relation towards the moral resurrection of Germany and Europe after the fall of fascism. It links the idea of democracy directly with the idea of contemporary art and at the same time it hands the criteria for this into the hands of an individual, i.e. one chosen curator, who every five years has under control an immense system and the power to chose as regards the condition and potential development trends of international aesthetic production. The establishment of M can therefore also be seen as European consciousness as regards a new decisive moment in its history. The novelty of its organisational structure can be found in the fluidity and the possibility to move the centre of power, which changes the place of the event every two years. The financial policy of the event is always open towards new bidders. The structure of decision making is based in such a way that a relatively fixed honorary international council (as a virtually present centre) negotiates with the national council of the host state. ‘The group curator’ should make sure that there is a difference in the views, and ensure a dialogue and not a thesis character of the event.

Apart from M, new biennial and triennial international exhibitions started to emerge all over the world. These exhibitions represent channels through which once isolated, subordinate or marginalised cultures can enter the central body of the international artistic system. These events are becoming an instrument of gathering, discussing and exchange of information and promise a possibility to redefine the history of contemporary art on the global level. The problem of contemporary art, related to the historical platform of industrialisation and post-industrialisation, very clearly points towards the fact that almost all cultures in this world have undergone a process of disintegration caused by the technological development, yet not all cultures had the political and economic conditions to develop and verify modern culture as a system of values which protects the individual from various local or global systems which try to win over the identity of the individual. This privilege was, as is generally known, held predominately by Western European and Northern American cultures, which have developed a strong and intelligent system of internationally linked institutions and which, with their knowledge and financial power still hold all the major cards for the development of aesthetic production. The paradox of globalisation is, that those cultures which have not integrated ‘modernity’ into the constitution of their collective cultural identity can become an easy target of power games and ecological destruction of globalisation. Regardless of this fact the present moment offers certain possibilities to anybody and every culture with a clearly defined idea as regards its identity, with an articulated memory and an efficient strategy, to make its way into the central ‘body’ of global consciousness, and to, according to its cultural and financial strength, integrate into the international cultural exchange system. And in this lies the charm of this wild and often aggressive moment with which the new millennia starts, for it gives the opportunity to all of those who have the knowledge and will to take advantage of it.

Regardless of all the stress and drama behind the scenes Slovenia and Ljubljana took the best advantage possible of the given opportunities offered by M 3 . The good and exciting stories are never created by a single player in the field, but with at least two or more, that is why we can not evaluate the success and takings of M 3 merely through this event, but we should view this through the interaction with the project of presenting the 2000+ Collection by the Modern Gallery, the project MSE - projects (Middle - South - East Projects) presented by the ©kuc Gallery, the events that took place in the Kapelica Gallery and other accompanying events of which three programmes of the Fifth Venue by TV Slovenija should be especially mentioned.

From the local point of observation

the constellation which formed around M 3 is not ‘from yesterday’,

but is a result of the development of a certain aesthetic production at

the local level that lasted for more than 20 years. At defining the type

of this production we are not dealing as much with the style characteristics

or the quality of artistic production, but more with the (ideological)

striving to overcome the isolation and reticence into the frames of the

national culture (in the East the integration of modernism into the system

of the national culture without international intertwining is more a rule

than an exception). In the 1980’s the movement to open the local aesthetic

production into the international space was lead mostly by artists with

the support of small, marginalised galleries, such as for example, the

leading gallery of this type, the ©kuc

Gallery. With the 1990’s and the process of post-socialist normalisation

a new institutionalised space undergoes a quick development and we can

also notice the emergence of a new profile of curators with a defined

international orientation.

In the beginning of the

1990’s the first break-through is made by the Kapelica

Gallery, which is taken over by Jurij Krpan. And then one after the

other projects emerge from SCCA-Ljubljana under the leadership of Lilijana

Stepanèiè and later on under Barbara Borèiæ, from the ©kuc Gallery, which

is under the new leadership of Gregor Podnar and from the Modern

Gallery under the leadership of Zdenka Badovinac. Parallel to the

internationalisation of the local system also a number of artists start

gaining on recognition (Irwin, Marjetica Potrè, Jo¾e Bar¹i, Marina Gr¾iniæ

& Aina ©mid, Marko Peljhan, Apolonija ©u¹tar¹iè, etc.), however their

success is not always a result of the support offered by the local system

but often this is a result of their individual strategies of survival,

which they have developed themselves or inherited from the 1980’s. On

the level of a successfully carried out institutionalised transition and

normalisation the progressive policy of the Modern Gallery, as a central

state institution, which understood the role which a strong institution

can play on the inside as well as on the outside, should be emphasised.

In the local context the Modern Gallery has, with exhibitions such as

Body and the East or U3 with the visiting curator Peter

Weibel, very quickly started drawing into the centre the creative energies

from the margins (the aesthetic guidelines of Kapelica and ©kuc galleries,

Irwin - New Collectivism, etc.) and towards the outside it started to

establish clearly defined criteria and conditions for the contextualisation

of the conceptual and post-conceptual Eastern European art in the dialogue

with the artistic, curatorial and museology trends with its visiting foreign

artists and projects such as the aforementioned Body and the East

and 2000+.

One of the reasons that Ljubljana gained the chance to host the European

project M 3, which by all means brings certain political advantages to

the state in its negotiations to join the European Union, is also a consequence

of the fact that within the last decade the aforementioned artists, curators

and institutions managed to place Slovenia on the map of international

cultural and artistic exchange with their international operations. On

the other hand we are all aware, that even though it is well covered in

the media, contemporary aesthetic production is not the favourite of the

official Slovene cultural policy and that the major part of the Slovene

culture is still determined by the mentality of closing oneself in and

protecting some sort of autonomous pillars of the Slovene national culture,

which is constantly under threat from imperialistic interests of neighbouring

cultures or the destructive influences of the popular, predominately American

media culture. As opposed to Western Europe, where contemporary art has

a clearly defined ideological function especially in the context of foreign

policy, the contemporary aesthetic production in the East is dealt with

as an epidemic, which should constantly be controlled if not even eliminated.

In the light of thus placed constellations it was therefore very amusing

to observe the internal development of events which this summer lead to

a true golden age of contemporary art in the streets, galleries and museums

all across Ljubljana.

One of the reasons that Ljubljana gained the chance to host the European

project M 3, which by all means brings certain political advantages to

the state in its negotiations to join the European Union, is also a consequence

of the fact that within the last decade the aforementioned artists, curators

and institutions managed to place Slovenia on the map of international

cultural and artistic exchange with their international operations. On

the other hand we are all aware, that even though it is well covered in

the media, contemporary aesthetic production is not the favourite of the

official Slovene cultural policy and that the major part of the Slovene

culture is still determined by the mentality of closing oneself in and

protecting some sort of autonomous pillars of the Slovene national culture,

which is constantly under threat from imperialistic interests of neighbouring

cultures or the destructive influences of the popular, predominately American

media culture. As opposed to Western Europe, where contemporary art has

a clearly defined ideological function especially in the context of foreign

policy, the contemporary aesthetic production in the East is dealt with

as an epidemic, which should constantly be controlled if not even eliminated.

In the light of thus placed constellations it was therefore very amusing

to observe the internal development of events which this summer lead to

a true golden age of contemporary art in the streets, galleries and museums

all across Ljubljana.

It was obvious that a part of the Slovene cultural establishment (it was represented also through the national council) decided to host M 3 from vulgar political reasons, without truly understanding the political and cultural role of contemporary art in the context of the developed world. It was some sort of a formal approach to the cultural ideology of Europe without a true will to confront its contents. This can be best reflected in the extremely weak reflection of this state ‘mega’ event, especially from the point of view of the local academic and critic establishment. Such a relation reflects the character of submission, which was often described by the ‘Slovene Lacanists’ as a typical relation of the subject to the socialist government. On one side everybody in socialism (even the leaders) communicated through an unwritten, yet generally accepted consensus that the government should not be taken seriously, yet at the same time we operated within the rules of the game which was defined by the government. We are beginning to act similarly today. On one hand we would like to make fun and grimace over the depersonalised ideologies of the West, while on the other hand we are prepared to, in the name of the prosperity offered by this same ideology, subordinate to its every whim.

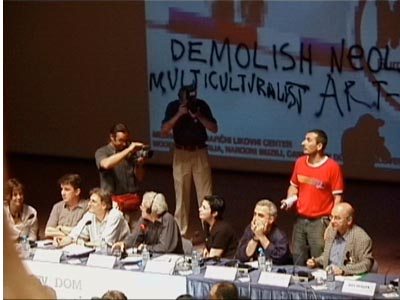

The M 3 experience revealed the complexity and potential conflicts in relations, which appear at the true confrontation of the local and global models of cultural production. This potential conflict would emerge if we started to seriously (and not only representatively) ask ourselves as regards the contents of this meeting. Therefore it is not surprising that not only the local structures did not want to let themselves into a dialogue as regards the content, but that also the four curators who were responsible for the conceptual preparation and material execution of the project tried to elegantly avoid this issue. In the first line the decision that the galleries ©kuc and Kapelica were excluded from the exhibition is very loquacious (see the comments of their directors published in platformaSCCA; Manifesta in our Backyard). These two galleries certainly present the most vital domain of contemporary aesthetic production in Ljubljana and M 3 could take advantage of them at least as a symbolically marked area for various forms of mediating the event. In this case the chiefs of M 3 acted similarly as various European non-government organisations, which go into endangered areas in order to salvage the civil rights of the local population but soon start to co-operate with those structures of the local government which deny the people of these rights. The statements with which the four curators argued the theme of the event in the media (borderline syndrome) or the general characteristics of the event were very general and politically correct. The texts which they included into the catalogue of the event hardly deserve to be evaluated as professional and it is symptomatic that the most articulated text in the catalogue, which clearly defines the social and ethical aspect of the ‘borderline syndrome’ is the text by Slavoj ®i¾ek, a text which was written in the 1980’s. The symposium which was prepared by Renata Salecl and which promised the possibility of concentrated and articulated mediation of issues and problems which arose from the event, took place as late as July, when most of the local and international interested public have already left the town. The incentive of Irwin to organise a parallel critical reflection of the reception of M 3 by mobilising the local and international critical public came across resistance within the local frames as well as from the Manifesta curators, who, the closer the realisation of the project was, started behaving more and more ‘defensively’. The event, which to a certain extent disturbed the obvious course of the spectacle was the performance by Aleksander Brener, who stormed into the press conference a day before the opening, sprayed the projection screen, lied down on the table in front of the speakers and somehow let them know that they should shut up. Even though Brener’s performance was ignored, he - if we try to look at it positively and constructively - managed to touch the sole core of the problem. By writing ‘Demolish neoliberalist multiculturalist art system now’ on the projection screen Brener challenged the intellectual reflex of those who represented this system from behind the table. The statement itself is, if we read it from the aesthetic point of view, absurd and dadaistic and it immediately found a response from the public with a loud cry ‘What is the alternative?’. The dramaturgy of the challenge itself and the direct response defines Brener’s performance as a successful one according to all criteria which are available to us. The reading of course depends on the fact whether we see Brener as a dangerous political activist and a potential terrorist or an artist who wants to draw attention to the moral crisis of the neo-liberal artistic system, it’s duality and controversy, which is shown through the dilemma how to get the declarative anti-representation artistic trends of the 1990’s into a controllable structure of large scale new systems of ideological representation. He succeeded in the challenge also on a more subtle level. He managed to make the curators, who based the entire manifestation around the issue of borders, border behaviour and defence strategies and who set works of art all around (works of art that pull down all possible aesthetic and social borders and where almost everything is possible), to, ‘under the spotlights of their own spectacle’, defensively react to an unpredicted, yet still aesthetically structured event which very clearly articulated the problem outlined in the theme of the event with the placement on the ‘border’ of the event itself (financially, programme-wise). The M 3 ‘border’ guards had the chance for an elegant neo-liberal solution, i.e. the inclusion of the Brener action, the material ‘damages’ of which amounted to approximately the same as the price of other (individual) artefacts, into the official programme of the event. The question is of course why did they decide otherwise and what does this mean. It would truly be interesting to get to know the ‘Big brother’ who suggested this decision.

The hosting of M 3 in Ljubljana can be evaluated as extremely successful and an unforgettable event. This became true due to the complexity of issues, which it brought forth and due to the insight into the broad reality of relations which it enabled. In his diaries Gustav Flaubert once wrote (at least this is stated by Julian Barnes in his renown novel Flaubert’s Parrot) that ‘internationalists are the Jesuits of the future’. Yesterday’s ‘internationalists’, today’s ‘globalists’ are also in a way the Jesuits of the present and if we ever deal with today’s international system of art and we try to enter it from the margins we are doomed if we do not take this into account and we do not develop the consciousness as regards the Machiavelism of relations which makes this work. The best defence in these relations is not showing disapproval, moralising or even closing the borders or building a Great Wall of China, but a very clearly defined negotiating position, cultural point of view or an artistic product. In the logic of negotiations and dealings with such fragile materials as values, ideas and art, we, the East Europeans are much less experienced than the ‘inventors of the matrix’ from the West, therefore the experience of M 3 should be taken seriously and should be repeated whenever the opportunity arises.

In any event we could be satisfied. Regardless of the outcome in the internal games of power and regardless of the possible recession blows at the level of local cultural policies, Ljubljana has experienced an aesthetic and informational boom which it will have to slowly and soberly digest. We have seen a lot of ‘good art’, while the local cultural ‘civil servants’ should be enthusiastic especially about the generally known evaluation of the international expert public, that the project 2000+ by the Modern Gallery has in a number of things overshadowed and overcome the conceptual and aesthetic effect of M 3 .

Aleksander

Brener: action, M3 press conference

Aleksander

Brener: action, M3 press conference

Ljubljana, 20th October

(Eda Èufer - dramaturgist, essayist)