Igor ©panjol

Manifesta in the living room

“‘Television’ then is best understood as the name of the institution that has arisen to manage and distribute the medium of video.”

Gregory Ulmer

‘They asked me to participate on this Manifesta thing. I don’t know why. They gave me a big, big screen, I asked why, they told you made an important work. I don’t know’(1) we are told by Joost Conijn through an embarrassed smile. The man is not burdened by curator’s concepts and does things in life that he likes. For example he constructed a plane and he thinks of himself more as a traveller than an artist. According to the opinion of those who do not support this segment of art, M is in its entirety more a traveller’s than an artistic event. Others, who feel that this kind of art production is close to them, have focused their reproaches on the problem of presenting the chosen works in museums, or to be more precise on the inappropriate presentation of to many so called documentary videos. And even though any sort of discussion as regards the meaning of a work of art must take into account the specifics of the media in which a certain work is made, at the lack of expert problematisation of the event and the analysis of the exhibited works, some sort of a representation discussion as regards the fiction and narration has anticipated the major part of all (more or less) expert opinions at the third issue of M. TV Slovenia (TVS), which has entered this event with three programmes of Peto prizori¹èe (Fifth Venue) has, in the same instance offered (almost the only) media space for such discussions as well as an interesting solution to the presentation of projects arising from the moving pictures medium.

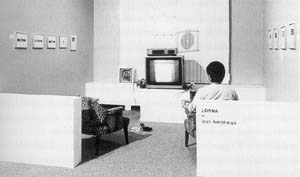

For many years it was customary

to show video art on small monitors in a corner of a gallery. Through

time the video format (with the development of the loop tape and the improvement

of the projector’s quality) managed to gain a larger part of the museum

area, by pushing aside paintings and sculptures. In comparison to traditional

artistic forms closed circuit video installations, video sculptures and

video ambience have, due to their comfort and new communication dimensions,

with no problems what so ever managed to gain the necessary attention

of the public. However, video projections (some like to wrongly call them

video installations) present a larger problem for the average visitor.

In the exhibition halls, in which they take place, it is not taken care

of (or it is only poorly taken care of) the seats, air conditioning and

proper darkness, the quality of the picture and sound is not constant

and the public is stepping in or out, or are just peeking from behind

the curtains all of the time. Usually the projected videos are longer

and run with a loop, so that at our entrance we, as a rule miss more or

less of the beginning, which of course, once we have seen the video to

the end, we are not interested in watching. The only case, in which the

loop procedure was of any sense at M 3, because it represented a basic

integral part of the artistic work, was the video FF/REW (1988)

by Ena Liis Semper, in which the authoress takes advantage of the time

manipulation possibility of the medium by destroying the linear and narrative

structure of the shown events. Projections without a loop are an even

worse possibility, for apart from this awkwardness they also demand from

the viewer the time to rewind the tape to the beginning. In short, every

attempt of a concentrated reception of a video projection in a gallery

is doomed at the very beginning. And there were a lot of video projections

at this years M, in the opinion of some too many.(2)

However, more that

the sheer numbers, the problem as far as the visitors were concerned lay

in the inappropriate presentation, with which this circle was soon brought

to an end: alongside the unfriendly conditions of perception very video

seemed longer than it really was, so that the quantity of works intended

for viewing became uncontrollable.

As already stated the ‘video film’ Airplane (2000) by Joost Conijn could be seen in the central hall of the Museum of Modern Art. This largest and most representative part of all M scenes, even though it was already architecturally planned more for social events then exhibiting works of art, was this time in darkness and changed into some sort of a cinema. With this they supposedly - in the same way as in the larger part of other museum premises - ensured the conditions for an in depth view of the chosen works, which demand ‘enormous concentration and enormous time’ from the visitors, however it enables them to establish an ‘intellectual appointment’ towards contemporary art.(3)

Even though scientifically valid evidence exists as regards the differences in the experience of a cinema screen and the experience of a television screen (from the technical difference in the forms of coding the visual information to phenomenological presumptions), the simulation of experiencing cinema perceptions in museums (by the way this is not a novelty which M brought forth) often proves to be difficult. It is legitimate only in the event of exhibiting works of those contemporary artists who flirt with entertainment and spectacle codes of commercial cinematography. However, the generation of artists presented at M use the video not to play with cinema codes but to play with the classical film vocabulary, especially editing. This is most obviously performed by Mathias Müller in his Vacancy (1999) where he combines his own footage of Brasilia with the so called found-footage. On the other hand some works seek for approaches in the ‘stone age’ of film, where a static camera is placed in front of the event or speaker who is filmed (Adrian Paci, Albanian Stories, 1997).

In such circumstances it is

not surprising that ‘on average the visit ends in less than a minute’(4)

and that theoreticians started treating the exhibitions as a dispositive

in which a constellation which forces into ‘inter-passivity’(5)

can emerge. A somewhat older approach of Fredric Jameson - he deals with

video through the concept of boredom as an aesthetic response and a phenomenological

problem - seems to be more appropriate, especially in the relation to

the theme of M 3: ‘Even taken in the narrower realm of cultural reception,

boredom with a particular kind of work or style or content can always

be used productively as a precious symptom of our own existential, ideological,

and cultural limits, an index of what has to be refused in the way of

other people’s cultural practices and their threat to our own rationalisations

about the nature and value of art.’(6)

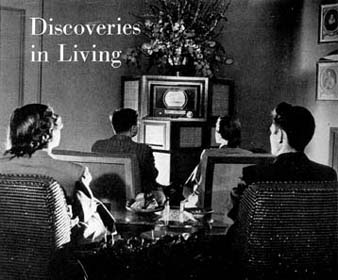

Therefore an interesting

change appeared. A change where we in the museums were witnesses to ‘surfing’

through rooms - ‘I look behind a curtain, draw it shut and go to the next

one’(7) - a perception typical of television, while on the

other hand television, with its programme Fifth Venue offered us

an in depth view of the same works in the comfort of our homes, where

viewers could ‘experience by themselves that contemporary art has more

to do with them, than it seems if they are just observing it from afar’(8)

and on top of that it also offered explanations of the shown works, which

are so often badly needed for contemporary art. At TVS they realised that

reflection is a constituent part of contemporary art and at this they

have also shown how much critical thought lags behind the development

of production powers, which constantly broaden the technological means

and expressional range of their operation.

Most of the authors were glad to co-operate in Fifth Venue. In their interviews they answered the question ‘why video?’ by emphasising the practicality and accessibility of video - because it is an extremely nomadic event, the advantage of video as regards the practicality of transport should not be neglected - and thus touched the problem as regards the conditions of artistic production and their influence on defining the meaning of a work of art. The curators of M 3, the duty of whom was to understand the specific meaning of a work of art and exhibit this work in a way which will reduce the danger of misinterpreting the meaning as well as minimise the misunderstandings between the work of art and the audience, defended the (dis)proportion between video and other means of expression with the fact that the new generation of young artists - i.e. those to whom M should especially be made available for representation - find video to be the closest means of expression, for they grew up alongside its development which went into the direction of mass accessibility and everyday presence. Therefore this was not a matter of choice to divide and categorise between video and traditional artistic techniques, but a desire to pass on our everyday experience, a spontaneous and unburdened use of video technology in the reproduction of reality, i.e. the choice of the medium which finds it the easiest to break into the everyday reality.

The statements of artists and art experts focused on the relation between the conditions of production and the conditions or circumstances of the reception of a work of art and have therefore at the same time brought forth the decisive influence of this relation upon the understanding of exhibited works. Through the connection of form, meaning and function of a work of art, the key to understanding the role of the observer and the problem of the museum as a scene for exhibiting works which are made in the moving pictures medium, was offered to us by the video Old House (1999) by Nasrin Tabatabai, which - as a sort of homage to Rotterdam, the town in which M has been conceived and exhibited for the first time - was shown at the beginning of each of the three Fifth Venue programmes. This video was made for the artist’s neighbour, shop owner Haci Ceyhan. During the filming Ceyhan took over the role of scriptwriter and director, the roles which are usually given the value of authorship, while the artist was merely his assistant. The video was therefore, in the same way as innumerable works in the history of art, made to order and this fact marked the function of this work (show his new living environment to his relatives in Turkey) as well as its meaning (from the national side to strengthen the distance of an immigrant, from the viewpoint of a person living in the town the feeling of pride over the architectural achievements). Nasrin Tabatabai did not record this video ‘for herself’ and it became a work of art only after the shooting of it was completed. Its showing on the monitor in the National Museum of Slovenia showed how the original user of the work of art does not necessarily define also its meaning or status as a work of art. Transmission on TVS has, apart from offering a piece of information as regards the person who ordered the video, also added a statement by the artist as regards how she (during the creation process) saw the relationship between her and the person who ordered the video. This undoubtedly influenced our perception of the work of art, however it did not factually change its character. By learning how the formal realisation of the work arose the meaning of the video was enriched, deepened and broadened, but not changed. A change in the meaning could be influenced only by a change in the form, but in this case this would not be the same work of art even though the form of transmission is only one of the three constituent elements of every video projection (the other two are contextualisation and the material itself).

The upgrade of the regular

television monitoring of M 3 with the project Fifth Venue showed

an optimistic tendency of the national television for co-operating with

artists at the creation of ‘“different” programmes, which are not standardised

with established codes of television programming’(9) as well

as a continuation of the television’s rich tradition of producing and

presenting art videos and thematic programmes on video art in Slovenia.

For almost all of the

projects, projected in the galleries through large-scale video projectors

and small monitors (these were in most cases placed in hallways or museum

lobbies), television proved itself as a better exhibition space. Of course,

this was by no means a solution just for the sake of it; the projects

were comparable and close to the television medium and they worked better

in this medium, at which the most ‘television-wise’ project was realised

by Anri Sala. His Nocturnes (1999) is a sort of an anguish video

noir, in which the stories told by two men metaphorically intertwine.

The story of one outlines the problem of murder, which is seen by Michel

Serres as the initiating event and advent of representation. Serres asks

himself: ‘Is there anything new about the rep or rap given murder in our

most current, media context of serial repetition? Or are we still stuck

in the age-old context or contest between iconoclasts that right from

the start of our mass culture has mixed the sense of “mass” as group and

as a metonym for the media, with the word’s destinal meaning of Christian

Communion?’(10). The answer is given by Salas interviewee who

we can see only the hands of all of the time, when he, at the end of his

soul-stirring story of his co-operation in the last Balkan war says: ‘For

me this is Playstation.’

The minimalist and to all extents

simple directors approach of Zemira Alajbegoviæ Peèovnik (it

is important to state that she is a video artist and the authoress of

Podobe (Images), the most important series of television programmes

on video production in Slovenia) on one hand enables all of the chosen

videos to be properly expressed, while on the other hand because of the

classical and official form - they are shown mostly in the choice of colours

and neutral backgrounds of studio shots - they fit into the other four

venues.

If we are a bit mean

and congratulate TVS as the only representative of the so called local

scene which appropriately responded to M (maybe its advantage was in the

fact that it is not in the strictest sense an artistic institution and

it could therefore act less burdened, and from the very same reason the

international curratorial team did not produce ‘energies of defence’ towards

it), we can in the same style also say that after all the statements we

are not surprised to find that we can say that all the lacks of the Fifth

Venue project can be ascribed to the joint points with other, classical

artistic venues. The authoress Vanesa Cvahte really acted as the curator

of the programmes (this was admitted to her at the beginning of the first

programme also by Francesco Bonami, curator of M 3) in the sense that

she showed a certain choice of the already chosen videos as regards the

set genres. As a consequence of this classical curatorial approach (gate

keeper), which is in opposition to the contemporary tendencies of video

curatorship according to the open archive principle, we did not see on

television for example the excellent Strange Message from Another Star

by Veli Granö, a melancholic story about a man whose entire life was marked

by a dream to build a rocket and settle another planet, or the media critical

videos of Phil Collins which were - doomed to a catastrophic placing within

the museum collection of the Museum of Modern Art (without any sort of

a contextual reason for doing so) - calling out for an additional alternative

opportunity for presentation.

Also the division of works on conceptual, documentary and avant-garde seems plausible only from the museum viewpoint. The last case of such definitions for any cost is presented by the permanent exhibition at the London Tate Modern, where they were lost for a better answer and they divided the works according to their classical motifs (nudes, portraits, landscapes and still life) and were then in some most urgent cases forced to break this division. The production of electronic media is already by its nature opposed to differ between documentary (narrative) and fiction. New media (and video was also once a new medium) abolished fiction as one of the basic categories of aesthetics and since then the division between fiction and non-fiction seems to be equally out of fashion as differing between art and life. After all, already Walter Benjamin showed that the ‘apparatus’ (in his time the concept of media did not yet exist) destroys the authenticity. It seems that so called documentary videos offered at M, even though they do not project fictive time and do not deal with film type fiction, still, through their aesthetic ideology and effects, promote some sort of a remnant of fiction which can be seen in the form of documentary constituted time. Luckily Benjamin was understood very well at TVS when he stated: ‘One might generalise by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced’(11). And in this the mission and beauty of the television as an exhibition space of contemporary art lay hidden.

1. Vanesa Cvahte,

Peto prizori¹èe: Manifesta 3, part 2, TV Slovenia, 1, Ljubljana,

16th August 2000.

2. 'She was less enthusiastic about the work on video tape. The two visitors

from Switzerland were also of the opinion that there was to much video

and not enough of everything else at the biennial, …' in: Irena Brejc,

'Ne brez vodnika po razstavi', Dnevnik, 28th August 2000.

3. Cf. the statement of Maria Hlavajova in: Vanesa Cvahte, Peto prizori¹èe:

Manifesta 3, part 1, TV Slovenia, 1, Ljubljana, 19th July 2000.

4. Delo, 10th August 2000.

5. The philosopher Robert Pfaller explains that this is an opposition

to inter-activity, when we have a work of art and an observer. The observer's

passivity at consuming the works of art leaves the observer and travels

to the work of art. Thus, production and consumption of the work of art

are brought to an end - the work of art tells the observer, that it is

finished. The observer has nothing left to do and can go home. The work

of art has already seen itself. Numerous videos are therefore not seen

in their entirety, but we look at only a part of them, and yet we have

a feeling, that we have gained something. The part that we have not watched,

has seen itself and therefore we have not got a bad feeling that we have

missed anything. (…) These video projections signal to the viewer that

he can do something else. Vanesa Cvahte, Peto prizori¹èe: Manifesta

3, Part 3. TV Slovenia, 1, Ljubljana, 20th September 2000.

6. Fredric Jameson, Postmodernizem, Analecta, Ljubljana, 1992,

p. 136.

7. Robert Pfaller in: Vanesa Cvahte, Peto prizori¹èe: Manifesta

3, part 3, TV Slovenia, 1, Ljubljana, 20th September 2000. 8. Melita Zajc,

'Peto prizori¹èe', Delo, 22nd July 2000.

9. Vanesa Cvahte, 'Fifth Venue.Television as an exhibition space of contemporary

arts', Exhibition Guidebook, Ed. by Igor Zabel, Cankarjev dom,

Ljubljana, 2000.

10. 'Theory on TV: Making Killing. Laurence A. Rickels talks with Michel

Serres', Artforum, No. 8, April 1995.

11. Walter Benjamin, 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction',

in: H. Arendt (ed.), Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, London, 1973.

(Igor ©panjol - Student of History of Art and Sociology of Culture at the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana)