| Nata╣a IliŠ & Dejan Kr╣iŠ |

|

| Political Practices

of Art |

Chances for Alternative Culture

In regard to cultural production, the term 'alternative'

is usually linked to notions such as anti-art, avant-garde,

neo-avant-garde, contra-culture, to everything and anything

which is different in form and content, progressive, radical,

which gets out of the mainstream and opposes the establishment,

the traditional bourgeois high culture. But in today's circumstances

of culturalising everything, in a situation when every 'avant-garde'

or 'subversive' act is immediately absorbed as a fashion,

an exclusively cultural and temporary alternative, there is

no alternative culture. Alternative culture existed when there

still were alternative ideas about the order of society, ideas

of alternative politics. Or, it might be better to say that

alternative culture is to be articulated only if there is

a policy that articulates the alternative to the truly existent

capitalism. In the current situation cultural and artistic

production can remain alternative not by the virtues of new,

different, unusual forms or ways of expression, but exclusively

in a political sense.

In its heroic period of 1970s and 1980s, the alternative

cultural movements in Yugoslavia acted against official institutions

or at least apart from them. Self-organising and activism

were politically engaged, but not as 'a battle against the

darkness of Communist totalitarianism', but, paradoxically

for the state whose official ideology was 'self-management',

as a fight for complete self-realisation of individuals and

culture, against the real bureaucratic limitations. Alternative

cultural movement was indeed taking socialist ideology more

seriously than the cynical political Úlite in power did. Paradoxically,

deeply politicised, alternative, sub-cultural movements of

'70s and '80s in the East actually disintegrated at the moment

of their supposed triumph - with the introduction of parliamentary

democracy and the 'return of capitalism'.

Instead of ' the normal' integration of the previously alternative

culture into the market mainstream, a process started in Croatia

in the late '80s, in the '90s we had witnessed its complete

breakdown. With new nationalist government, within the general

suffocation of all liberal-democratic tendencies, but also

due to the brutal early capitalistic economy, the institutional

framework through which 'other', 'alternative' cultural scene

managed to act, was completely destroyed.

Within the independent Croatian civil scene in the '90s, often

called the alternative scene(1), the notion of alternative

was used differently in two broad periods. The first one,

in accordance to the general regression, characteristic of

the period of the Croatian Democratic Community party's

rule, is actually a continuation of '70s ideology that perceives

alternative culture as the low opposition to high, Úlite,

institutional culture. That scene, roughly identified with

eco/punk/hardcore/anarcho groups and movements, really was

marginal and marginalised, completely outside of the funding

system, which it had slowly entered only after the establishment

of the Open Society Institute (OSI) in Croatia in 1994.

In the second period, the alternative ceased to be synonymous

with the marginal and the sub-cultural and it developed specific

political meanings, regularly strongly based in ethical demands

for non-violence, equality, multi-ethnicity, non-hierarchical

structures, etc. Unfortunately, OSI-Croatia mostly held onto

the liberal, bourgeois mainstream position that had not been

quite receptive for politicised, alternative cultural and

political praxis. The leading people of OSI Croatia did not

have a clear cultural policy, and starting from their cultural-Úlite

positions and the political phantasm about local liberals

being capable of winning the elections, they perceived the

alternative scene as something necessary, yet unwelcome. They

hardly acknowledged or financially supported alternative culture,

and when they did, it was often by miserable funds and under

humiliating conditions. Amongst the leading people of OSI

Croatia, the alternative in the culture was perceived as a

system of parallel institutions that were not nationalistic

or statehood-oriented, but their activities were limited to

fill in the gaps left open by the state and its conservative

institutions.

Therefore, in Croatia of the '90s, the real alternative had

been born out of resistance to Soros cultural phantasms, as

well as to state phantasms; out of the critique of nationalistic

politics and culture, but also in resistance to parliamentary

opposition that had not for a second dared to seriously question

the broader ideological framework and rhetoric of Tuman's

rule.

Subversive strategies of Sanja IvekoviŠ

Amongst the very few contemporary Croatian art practices

that are close to the ideological position that defines itself

as alternative, the most consistent is without a doubt the

art practice of Sanja IvekoviŠ. With her works in the '90s

the artist had tried to reply to the intellectual urgency,

which is even more dramatic when considering the circumstances

under which those performing 'the social function of intellectuals'

have mobilised extreme right ideologies. Many of these works

were realised in various models of collaboration with organisations

that emerged within a broader context of the alternative scene,

while official art institutions were involved in the processes

of its mediation. The production and reception of her artistic

projects has been outlining the sliding terrain of the transformation

of traditional political art into political practices of art.

It also includes all the uncertainties and shifting positions

of the attempt to pose the questions whose answers cannot

be announced in advance, but can only develop through a series

of failures. It is an effort not just to illustrate the political

thesis, thus making it clear to those who already know it,

but to include art into the political praxis, form new ideas

and spread them into society.

The struggle for uniqueness of the national culture fought

by right wing intellectuals has been realised as a struggle

against left cultural hegemony, interpreted as the foreign,

external element that threatens the purity of the national

culture/national identity. A vital part of the project of

cleaning up the national culture has been suppressing the

important part of history and producing a silent collective

amnesia.

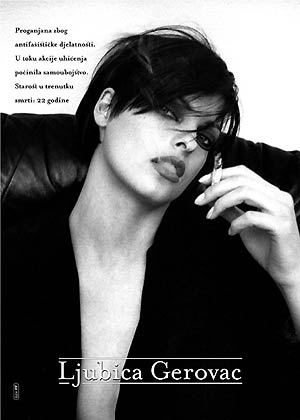

Sanja IvekoviŠ, Gen XX, 1997-2001 |

Sanja IvekoviŠ's project Gen XX has been realised

as advertisements published in various magazines. The women

in the photographs are professional models whose faces are

familiar to the contemporary audience, while the text accompanying

the photos presents National Heroines known to the generations

that lived in socialist ex-Yugoslavia, but have been completely

erased from the contemporary collective consciousness.

The manoeuvre that Sanja IvekoviŠ performs within the Gen

XX media action consists of appropriating the media talk

and subverting it by its own means. Using the media is always

a manipulation, a technical treatment of the given material

with a particular goal in mind. When the technical intervention

is of immediate social relevance, manipulation is a political

act (which it is by default within the media industry). Gen

XX turns this commonly accepted fact into its advantage,

appealing to people's sophistication, addressing a 'target

group' that takes pleasure in being taken seriously and should

not be left to advertising.(2)

Gen XX gives lessons in both history and media dwelling

in the imaginary space that shapes the formation of the public.

Its subversive tactics do not reside in the practice of provocation

but in its accommodation to the social codes and conventions

of everyday life informed by mass culture.

It is a certain translation from a specialised language into

the media code, re-translated by media recipients into their

own language of the every-day. The effectiveness of its communication

strategy consists of this translation based on the analysis

of the moment of performance and transmission of knowledge

in relation to the moment of the conception and of the research

itself.

Sanja IvekoviŠ, SOS Nada DimiŠ,

2000 |

The urban intervention SOS Nada DimiŠ was realised

in June 2000, at a time when bankruptcy cases have been heading

the news and the optimism caused by the change of the government

a few months earlier(3) did not drain out completely yet.

The work refers to the National Heroine Nada DimiŠ, a real

person killed in World War II for her anti-fascist activities,

but also to the factory named after her. The textile factory,

which traditionally employs mostly women, had been successfully

functioning under the name Nada DimiŠ throughout the socialistic

decades, but went into bankruptcy as Endi International,

which is the title it obtained in the '90s.

Renovation and re-lighting of the neon sign Nada DimiŠ at

the factory's fašade, in the situation when the state bureaucratically

administrated the bankruptcy procedure and the fates of hundreds

of pauperised, mostly middle-aged women who were about to

lose their jobs, was a highly symbolical act. To let the light

shine on the factory and its troubled workers functioned not

only as a reminder on the times when brutalities of the market

economy were not accepted as a natural and objective state

of things that can not be altered, but also as a call and

warning.

At the same time it was about a beautiful logo whose neon

lettering functioned as a personal signature, an unique and

proper sign, an authorisation of legal validity that links

the factory's name to the real person, Nada DimiŠ. To light

the logo with the name of the heroine forgotten and turned

into a brand name is not only about re-establishing her both

as a person and a role model in the male-dominated society,

but also about urban landscape appreciation. It shows a certain

sensitivity for urban layers of the past so crudely dismissed

in the renovations undertaken during the '90's in most of

the Eastern European 'metropolisis'.

Rosa Luxemburg at the Heart of Capitalism

Sanja IvekoviŠ's biggest public art project so far, Lady

Rosa of Luxembourg, shows many of the artist's preoccupations

expressed in her earlier works. The work also testifies to

a certain shift, in many ways connected to the different context

of the Western social and art system. Lady Rosa of Luxembourg

was realised in the spring of 2001 within the exhibition Luxembourg,

Les Luxembourgeois that intended to define and question

the issue of the national identity of Luxembourg. The exhibition

was organised by MusÚe d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg.

Like Gen XX and Nada DimiŠ File, it also links

the issues of social remembrance and amnesia to the women's

position in the society. The project has been realised as

a copy of the Luxembourg monument GŰlle Fra (Golden Lady),

the strong national symbol of Luxembourg's independence and

resistance erected in commemoration of the victims of World

War I.

The work was first conceived during Manifesta 2 in Luxembourg

in 1997, when the artist proposed to place the statute of

GŰlle Fra in front of the women's shelter during the

duration of the exhibition. Since it was not possible to realise

this, Sanja IvekoviŠ initiated an international project (Women's

House), which was developed in close collaboration with

women's non-government organisations, shelters for women victims

of domestic violence and women who sought help in shelters

in Zagreb and Luxembourg. The artist exhibited plaster casts

of the heads of the women with whom she had been working in

shelters, mimicking traditional high-art exhibition set up

and at the same time elevating anonymous traumatic experience

to the level of universal social relevance.

The original monument of GŰlle Fra, dating from 1920's,

represents an elegant female figure standing at the high obelisk,

draped in clothes through which the outlines of her body are

clearly visible. As such, it belongs to the corpus of monuments

developed during the French Revolution and has become representative

for forms of political constitution and political iconography,

characterised by an allegorised femininity that signifies

freedom, the Republic, as well as the nation or that upon

which a nation's self-understanding can be grounded, that

is, arts and sciences.

The replica was staged not far from the original monument,

from which it differs not only in the materials used (golden

polyester for the figure and wood and iron for the obelisk

and base), but also in a few other important details. The

female figure is clearly pregnant, the original captions on

the monument's base are replaced by words in French (le rÚsistance,

la justice, la libertÚ, la indÚpendence), German (Kitch, Kultur,

Kapital, Kunst) and English (whore, bitch, Madonna, virgin),

and the Golden Lady is subtly renamed to Rosa Luxemburg

and thus moved from the abstract allegorical context into

concrete historical circumstances.

Lady Rosa of Luxembourg was installed on 31st March

2001 and in the weeks to follow it had triggered a violent

set of polemics within the Luxembourg's media. At certain

moments even the question of resignation of the Luxembourg's

Minister of Culture, who had been against the calls to demolish

the monument, had been raised, and before the summer started

press clippings had filled several hundreds pages. The polemic

started when anti-fascists veterans and liberal-national politicians

and men of prominence proclaimed the newly erected, temporary

monument to be blasphemy that makes a mockery out of the Luxembourg

resistance and its victims in both world wars. Strangely enough,

it seems that the most violent attacks were not provoked by

the figure of the pregnant woman, but by the text in three

languages. At the beginning, most photos in the press had

shown only the monument's base with the text, while the figure

of the pregnant woman at the top of the obelisk had often

not been represented at all. What is it about the text by

Sanja IvekoviŠ that provoked such strong reactions? Or maybe

the text had served just as an excuse for the aggression whose

real object is a golden woman whose blatant pregnancy insults

not only the sophisticated aesthetic feelings, but also the

national values represented by allegorical feminine?

The text at the monument's base alludes the complex and problematic

issue of language as the ground for a national identity of

Luxembourg, but it also points towards the entanglement of

the modern construction of the ostensibly natural two sexes

and the construction of the modern nation-state. The transitions

between culture, politics and political representations are

fluid and the political is always already determined by that

with which it is supposed to have nothing to do, and the text

quite clearly exposes the problematic 'naturalness' of the

national monument.

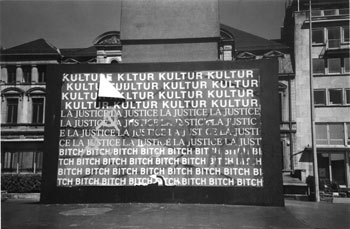

Sanja IvekoviŠ, Lady Rosa of Luxemourg,

2000 |

The English text locates stereotypes about women (Madonna,

whore, bitch, virgin), the French words (le rÚsistance, la

justice, la libertÚ, la indÚpendence) point towards the realm

of political values that the feminine figure allegorically

represents while in reality women had been excluded from them,

while the German text (Kitsch, Kultur, Kapital, Kunst) comments

the cultural production and the production of culture that

lies at the very base of such a constellation.

By naming her sculpture after Rosa Luxemburg, the artist unmasks

not only the fact that women are symbolically constructed

as the symbolic bearers of national history (but at the same

time they are denied any direct relation to national agency),

but it also affirms the revolutionary politics of Rosa Luxemburg

and questions the very notion of national identity. Rosa Luxemburg,

a 'left terrorist', as she was proclaimed in one of the angry

letters in Luxembourg's daily press, deeply annoys the myth

of capitalist ways of production, and capitalism as a social

order supposedly being capable to reproduce without non-economical

oppressions. As a pregnant woman, she threatens to affect

the framework of the collective memory that consists of things

which are 'always already' understandable and reproducible,

without having to be made explicit or explained in words.

Her words 'Today we can seriously set about destroying

capitalism once and for all' are exactly those that are

not to be heard in today's Luxembourg, the embodiment of smooth

economical functioning and order, just as they were not to

be heard in Europe of 1919.

Judging by the reactions, to erect this public monument is

an act just as serious as it was at the time when the original

monument had been erected, even more so when erected by the

artist who is also an Other - woman, artist, feminist, coming

from the Balkans, from a country of doubtful democratic traditions

- an act that seriously challenges the aseptic (multi)cultural

consensus at the heart of Europe.

But the set of polemics also shows how these arguments were

largely ignored and the emphasis generally shifted to less

relevant concerns. An increasing number of leftist intellectuals

and women's groups got engaged in the defence of the temporary

public monument in the name of abstract artistic freedom,

thus excluding most effectively all those unpleasant questions

that the Lady Rosa of Luxembourg tried to open. Such

an approach had situated the whole story within the framework

that the artistic and general community knows how to deal

with, turning it in an 'undemocratic' incident quickly channelled

back into the system. The fact that the system's efficiency

is not to be doubted is best confirmed by the events that

followed after the exhibition closing, when the monument was

finally removed, at the relief of most involved parties.

The show is over, let's get back to more practical things.

Where to place the monument? The Museum had offered the artist

that it will take care of it, asking the artists to donate

it in return. By that time it was quite clear that it is in

the community's best interest to prevent further irritations,

so Museum's officials suggested not to display the monument

until some appropriate exhibition in the future, which the

artist did not accept. Lady Rosa of Luxembourg ended

up in the courtyard of the women's shelter in Luxembourg.

Which, paradoxically, brings us back to the original proposal

of Manifesta 2. But the circumstances are quite different.

Traditional allegorical values of the original female figure

are strongly fixed within its physical existence as an artistic

object. As for its symbolical values, an initiative to legally

endow the state authorities with copyrights over GŰlle

Fra was instigated in the media, ensuring not only the

protection of the highest national values from future blasphemies,

but also its position within the market economy's rules of

the game. And it is quite obvious that the pregnant replica

located in a women's shelter, away from the public eyes, does

not trigger questions of displacement as the original monument

would. Then again, the women's shelter seems to be a place

quite appropriate for it.

1. Projects like Anti-war Campaign Croatia,

pop-political magazine Arkzin, Zagreb Anarchistic movement,

Autonomous Cultural Factory - Attack, festival of alternative

street theatre FAKI, and many other feminist, ecological,

anti-war, anarchistic organisations, groups, initiatives and

movements.

2. Advertisements were published in magazines such as Arkzin,

Kruh i ruże, Zaposlena and Frakcija. They emerged

within the circle of the Zagreb independent civil scene of

the 1990's that accentuated the openness to the Other at the

time of ethnic intolerance, war, violence, and conservative

attacks on gender and sexual rights and freedom until recently

thought of as obtained and unquestionable.

3. In January 2000 a right-wing government in power for a

decade lost the election.

Nata╣a IliŠ: art historian, independent curator and art critic,

founding member of NGO for visual arts What, How & for

Whom.

Dejan Kr╣iŠ: art historian, designer and Editor of design

studio/publishing house Arkzin.

|