| Lev Kreft |

|

| The Avant-Garde

is Mainstream |

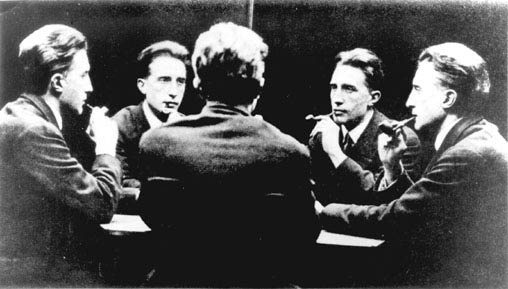

Marcel Duchamp: Marcel Duchamp author d'une

table, 1997

Lately I have heard the sentence 'The avant-garde has now

become the mainstream' so many times, that I have become rather

suspicious. We could trace its origins back to the sixties

and today it represents a repetition (tragedy of farce?),

as it was written down by the great canonist of modernistic

criticism Clement Greenberg in his essay Avant-Garde Attitudes

(1968) - and yet already this essay is a continuation of the

famous 1939 essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch. His evaluation

of the current artistic movements (which we today normally

call the neo-avant-garde) was that they no longer have a proper

opponent in academic art, because the avant-garde has completely

predominated the artistic scene. And because the avant-garde

remained on the scene with itself, it also applies solely

to itself, therefore plain novelties and spectacularity stepped

in place of qualitative criteria.

One can comprehend that something must be told twice, especially

if there is a period of forty years in between. But when dealing

with reiteration and not merely repetition one has a feeling

that some sort of a forced neurosis is calling a solution

in the form of a diagnosis for help. And the constant talk

about the mainstream avant-garde has already become a sort

of neurosis.

At first glance the statement is a completely normal ascertainment,

which almost should not be discussed. The historical avant-garde

appeared at the beginning of the 20th Century and was well

finished at the latest in the mid thirties. It finished by

the way, as many other things in that period. Following the

peak of radical modernism in the sixties, which supposedly

achieved a level of unchangeable eternity of the end of history,

an artistic movement appeared which was also called the avant-garde.

Whatever it was it was rightfully called the neo-avant-garde,

especially because it had chosen historical avant-garde as

its tradition and because it went into oblivion in the same

way (only a bit faster). At the latest at the beginning of

the eighties it was already announced that the sixties have

finished, and that the attempts to jump into the sky in the

name of utopic beliefs of any kind do not hold any ground

even in art - hence trans-avant-garde, which is a phenomenon

which is (to put it bluntly) a bit over the moon. This was

also one of the reasons why the new wave of attachment to

the historical avant-garde could not have an avant name, but

a retro name. The fact that at the end it arrived at the mainstream

avant-garde is a completely logical step, for at every step

from the historical concept of the avant-garde something went

amiss, and that, which was dismissed at first was its politicality

- its political politicality as well as its aesthetic politicality.

The political politicality of the avant-garde was utopic,

extreme and subversive. The avant-garde was undoubtedly a

political phenomenon, for it appeared publicly, it made its

appearance with political means, and it appeared in groups

- political parties. In his Ph.D. dissertation Miklavž Prosenc

defined the Dada group from Zürich as the following:

1. The members of the group were immigrants and have therefore

found themselves in an extreme situation.

2. As regards the nationalities, origins and professions the

group was a heterogeneous group.

3. It was not comprised only of writers but also of (fine

art) artists.

4. The group's main preoccupation was how to fill a cabaret

programme, which changed often and was comprised of individual

acts.

5. The behaviour of the members was 'extremist', for they

found themselves in an extraordinary situation, caused by

the war and the disintegration of the generally adopted rules.

6. The productions of the members of the group (to the extent

in which they were preserved in writing, whether in the form

of poems or prose text) can be hardly defined as literature,

and not only because they did not want to write 'literature'

and did not want to be 'artists', but because they a priori

placed themselves in opposition to any type of 'art' and with

their actions they were stating a revolt against art and literature.(1)

This was an a priori action against art, and if this was

truly the case this could by no means by an artistic programme,

on the contrary, the avant-garde did not need an artistic

programme, for (as stated by Tristan Tzara(2)) art and culture

of the West did not have to be demolished - they fell to pieces

by themselves. It was merely necessary to draw attention to

the fact that this has happened and trigger the consequences.

Amongst the consequences of the fall of art and culture (which

were based on their own autonomy and which founded this autonomy

in the inherently artistically-cultural superior aim) the

destruction of the autonomy and the transformation to non-artistic

and non-cultural goals was necessary.

Historical avant-garde is a politicisation, it enters the

sphere of politicality as an extreme political party. This

is also the mistake which was made by Peter Bürger in his

otherwise excellent and influential book (Theory of the

Avant-Garde) - he defined the historical avant-garde as

a left wing movement, which was in the 'historical interest'

of the working classes, instead of placing his money on political

extremism as Miklavž Prosenc did. Of course, one could say

that the Zürich Dada is an extreme case, however, it is not

that extreme for the pre-war futurism not to be it's equal

in this sense, let alone the post-war movements in the Soviet

Russia or the defeated Germany.

Where does the political extreme of the avant-gardes lay?

In the fact that they take politics as an (anti) aesthetic

event, process and procession, in which the boarder between

the artificial and real is lost, as well as the boarder between

the artificial and natural - a curved space, in which various

ways of existence of reality, also artistic meet, and in which

it becomes evident that the essence of every reality lies

in its appearance, that nothing is hidden behind the appearance

- except for the appearance itself, which is hidden, even

though it is obvious, behind the strange idea that behind

it lies a hidden and unclear essence.(3)

And where lies the aesthetic politicality of the historical

avant-garde? By all means in its anti-aestheticism and anti-artism,

and at the same time also in the retaliatory efflux of both

anti-postures into life, as stated also by Peter Bürger. One

should differ between anti-aestheticism and anti-artism. As

defined also by the Prague school (which differentiates between

the non-standardised and standardised aesthetics and between

various functions of all linguistic phenomena, including art)

anti-aestheticism is in opposition to the aesthetic function

as a dominant and hegemonistic function in art, which subordinates

all the other and possible artistic functions.(4) We are therefore

dealing with an assault upon the structuralisation of the

meaning values of the artistic work, which is comprised of

various meanings, yet under the domination of the aesthetic

function and in light of the value dictated by its dominant

meaning.

The anti-artistiness is intended for a special position, which

is attributed to art and works of art - this social position

of art and artistic works is (of course) a social expression

of an internal structure of art and works of art, which are,

in the sense of a 'pure aesthetic judgement of taste', organised

as an absolute monarchy.(5) A certain excellency belongs to

art, an excellency out of this world and therefore total autonomy

holds true for it, which means we are not permitted to use

the normal life standards for it - and because it is completely

autonomous and independent from the everyday usefulness, morality

or politicality it can play the role of the saviour in current

conflicts. The domination of the aesthetic function as a function

of 'absolute disinterest' and the total autonomy of art of

course had a social-political function - with these mechanisms

art became the social and political capital of the elite,

which thought of themselves as the aristocrats of the spirit.

The aesthetic politicality of the avant-garde directly and

knowingly attacks and demolishes the position of the aristocrats

of the spirit, who applied themselves with the salvation role

in the human progress and placed themselves in the function

of the arbiter of all spiritual matters. It this fact it is

political as much as it is political in its political politicality.

That is why these two components (the political and aesthetic

politicality) should not be taken as two components which

just happened to meet at the avant-garde. It is true that

we know of a whole line of political politicalities, which

have nothing to do with the aesthetic politicality, and also

the other way round a sufficient number of aesthetic politicalities

could be found (at least within radical modernism), even though

without the group party appearances and so clearly defined

extremisms as at the historic avant-garde. Therefore, nor

one nor the other, but both together are typical for the historical

avant-garde in itself, and both together operate subversively.

This subversion is not a result of political and aesthetic

extremism, but the consequence of the tension, which the togetherness

of the political and aesthetic politicality cause in the political.

In a well organised civil society the state and the society

are appropriately divided as are politics and culture; this

is also the case with the well defined Marxist base and superstructure.

Aesthetics has its privileged place in autonomy, the political

has its privileged place in politics; chosen and elected specialists

deal with one and the other. The subversion of the simultaneous

political and aesthetic politicality, which are both marked

with extremism or with the prefix of anti-politicality and

anti-aestheticism, is found in the fact that it impugns and

shows this division as unbearable.

Hegel states the following: 'The actual idea, the spirit,

which divides itself into two idea spheres of its notion,

the family and civil society, as on its finiteness,

to be from its ideal for itself an infinite actual

ghost, therefore assigns these two spheres the material of

this final actuality, individuals as a mass so that

the assignment is seen by the individual as mediated

through circumstances, self-will and the own choice of their

determination.'(6)

Our everyday conception (we could easily also say ideology)

is that we have a society that is independent from the state

and a state which was created by the society so that its conflicts

and differences could be set straight in an easier manner.

Society therefore elects a state according to its own image.

Hegel is believed to be an idealist and this belief is to

what the ghost that can be found in his state-legal philosophy

is normally ascribed to: the play is entered by a state-making

Spirit which is divided into family and civil society in such

a way that the subjectivation of people from personalities

into subjects seems mediated 'through circumstances, self-will

and own choice of determination'. When Marx started toying

with this point stated by Hegel, he tried to translate it

into prose and turn this prose around in such a way so that

we would reach the true image of things: people who form a

family and a civil society become individuals (subjects) in

this community - and from here onwards they create the state

for themselves. However, in opposition to the usual prose

Hegel is here a materialist and Marx and idealist, for the

Hegelian image of subjectivisation of the individuals into

subjects complies with the actual state of affairs, while

the Marxist (with the exception of Marx' later works) complies

with the ideological image of 'realism'.

For even though it seems and it most probably also is logical,

that at first individuals exist and only then their community,

it is still 'true' that in the modern era the political subjects

are produced by the state and not the other way round, that

the civil society always remains that pre-political background,

from which the state recruits human beings into politicality.

What Marx does with politicality is not to turn Hegel upside

down but he denounces the situation in which we stand on our

heads, with the demand that things should be oriented into

the right direction - society should take hold of the state

and abolish it, and thus leave the political and enter the

actual, human emancipation.

Because of its link between aesthetic and political politicality

(the assault of the autonomy of art with anti-art, political

party extremism with public political appearances) the historical

avant-garde has a different effect: the division on the state

and the civil society, from which a politicality seperated

from aestheticism is born, as well as the process of subjectivising

people into subjects is put under a question mark. The position

of the avant-garde is not a position of the authentic and

natural society in opposition to the corruption of politics

and the state, but also the position of politicality against

the state. This is a civil society movement, which does not

want to be a movement of the civil society, but a political

party with an anti-aesthetic and anti-state programme. Peter

Bürger is correct when he states that the historical avant-garde

stands on the social positions of the proletariat - except

to the extent, that it itself stands on the social positions

of the proletariat, while no one has seen the proletariat

on these positions as yet.

If we take into account the three ways of representation about

which Scott Lash speaks in his Sociology of Postmodernism,

we can place the avant-garde in a position where it is at

the same distance from the centre of modernism as well as

postmodernism. The starting paradigm of representation as

a process, in which the image of reality starts as an image

of a subject (in which reality is 'given') is aesthetic realism.

Lash ascertains that aesthetic realism 'is possible only on

the basis of three previous types of differentiations' in

which the cultural field 'must be divided from the social',

the aesthetic field from the theoretical, and 'the division

of secular culture from religious' is also a necessary precondition.(7)

However, the most important precondition in order for this

three fold differentiation to work at all is that it remains

invisible and unproblematic. Between the signifier, the signified

and the referent there should be no disharmony, the way from

a thing-in-itself through the subject-for-us to the image

of the object or sign for the object is smooth and does not

have any hurdles or problems. With modernism and postmodernism

the situation changes and the realistic lightness of representation

is turned into an issue, however, this takes place at two

different ends: 'The difference is in the fact that modernism

understands representations as some sort of a problem, while

postmodernism makes an issue out of reality itself.'(8)

Modernism abolishes the belief into a single image of the

world, i.e. an image which through a convention is believed

to be 'realistic', a similar image and an appropriate picture,

and researches the alternative methods of representation.

At this it does not question what should be represented in

the representation - there are only numerous ways of depicting

and the realistic way of depiction loses its absolute validity.

Postmodernism starts the way at its starting point: that,

which we believe to be an unproblematic process of presentation

and depiction, and which experiences various ways of presentation

and depiction in realism, is also in itself merely a convention.

'The real world', the world of concrete facts which should

be represented and commented upon in a right way is not the

beginning or the cause of various procedures of depicting

and marking the world but a result and a consequence of these

procedures.

The avant-garde with its historic procedures of abolishing

art in life and a simultaneous revolt that it wants to make

in life itself, does in fact use both approaches, the modernistic

and postmodernistic, but both only to a certain extent. In

realism art is an autonomous sphere in the sense of a sphere,

therefore it depicts reality; in modernism art is absolutely

autonomous, for it is art itself that is the only true reality

which gives the character of reality and with this the human

reality to all other spheres - this is where the idea of the

religion of art lies in; for the avant-garde in its radical

phase art as either a reflection or the only right world is

what should be left behind, deserted or demolished, so that

no two stones stay together. Reality is somewhere else, in

life, which is shown on one side as modernity of a new industrial

revolution (big city life, the factory rhythm, electric power,

the car chaos and flying, etc.), while on the other hand,

as a bad infinity of constant new failures and increasingly

fast changing and starting anew from scratch, which should

be finished. For the avant-garde the slogan that art should

be left for life does not mean that we should return to the

direct and unproblematic reality, on the contrary: the most

problematic is reality itself, which should be overthrown

and turned around. Life, into which it would wish to enter

is something which as such, does not yet exist, and that is

why the avant-garde is utopic. Finally, the conflict between

the Bolshevik central committee and the Russian avant-garde

originated from this. After the conflict the communist party

took over the leading role amongst the proletariat and later

on it took over the leading role in the new socialist culture.

The party ascertained that the heroic age is over, and that

the time has come for everybody to return to their natural

chores: the party should rule, the society should change and

produce. Artists should produce works of art and at this follow

the political plans of the leaders of the revolutionary transformation

- especially due to the fact that the world revolution did

not seem to appear, and the Soviet Russia was alone and surrounded

by enemies. If everybody would not take care of their chores,

the land of hope for the entire humanity would fail, that

is why discipline with the division of work was of utmost

importance. The avant-gardists attacked especially the division

of work (through which they were forced to be 'societal')

into the differentiation of chores, which took away any autonomous

function within the politicality. The central committee designated

art and especially the avant-garde a place in representing

the world within the frames of artistic autonomy, which accepted

the party representation of the world as 'reality'. From all

of the artistic elite of the time only the avant-garde accepted

the party representation of the world as 'reality', but at

the same time it was the only movement that did not accept

the division into the political and social sphere, which within

the social sphere defined the position of the artistic autonomy

to all artistic activities and tendencies including the avant-garde.

The dispute between the modernists and the party was about

the freedom of artistic expression, the dispute between the

avant-garde and the party regarded the freely accessible and

equal for all revolutionary politicality. The modernists did

not need to be differentiated they only needed to be subordinated,

for differentiation was already their natural environment

- the avant-gardists did not need to be subordinated, they

only needed to be differentiated, i.e. placed back - into

art.

To a certain extent the neo-avant-garde by itself de-politicised

the historical avant-garde. This was mainly performed through

the fact that it made the avant-garde it's own tradition and

thus institutionalised it. However, the neo-avant-garde had

it's own politicality in which the division on the (dirty)

politicality and savour sociality was already dominant. The

manner of the struggle of town guerrillas and terrorism, and

the manner of the struggle with the retreat into the new spirituality,

showed (in two extreme ways) that the neo-avant-garde which

belonged to such movements according to its own ideologies

and often also with its striving and public appearances, presented

emancipation as an abolishment of the political within the

social.(9)

All of the realistically existing ideological systems representing

the correctly organised reality pushed the historical avant-garde

back into artistic autonomy. This means that alongside Nazism

and Stalinism, which both used also extreme violence this

was also done by fascism and liberalism, which were less violent

- although not always. In its stronghold there is therefore

also something much more dangerous than wrong slogans, i.e.

the approach itself, which does not fit any of the political

systems of modernistic control of the societal. In the position

of the historical avant-garde lurks a view which reveals that

society is a handy product of that political structure which

created also artistic autonomy as a pleasant organised residence

from which art is not supposed to enter the dirty and dangerous

world. And it is not a fact that the state should be abolished

so the society could come to the power, rather one has to

operate politically in order for the society to be abolished.

In the relation to the postmodern indifference the avant-garde

political stand is unpleasant because it can not declare the

autonomy of art and society as some sort of simulacra, which

seemed to be reality, but now we have seen through them. Representations

in fact do have political power and this is why the avant-gardists

demand that art should meet life and not the deduction that

these representations are something weak, which could be deducted

from the ascertainment that representations do not show 'reality'.

The German ideologists must be mistaken when they think that

one can learn how to swim by forgetting gravity - and in a

similar manner the postmodernists imagine that we will forever

step out of the representation combats and enter the end of

history by forgetting 'reality'.

In the neo-avant-garde and in postmodernism the historical

politicality of the avant-garde was de-politicised and one

could almost say nationalised, and in this way the 20th Century

avant-garde could enter the cultural institutions, which take

care of the artistic values of the past. The historical avant-garde

really did not make it, as stated by Bürger, and in the beginning

of the 1930's it was defeated, however, from this defeat the

way did not lead into institutions but into oblivion. The

institutionalisation of the avant-gardes could be dealt with

only when the historical avant-garde became a thing of the

past. And it became a thing of the past when it was

generally accepted, that the sell by date of its concept of

aesthetisation of politics and politisation of aesthetics,

was long overdue.

When we say today that the 'avant-garde became mainstream'

we do not think only that the historical avant-garde has become

a part of the great art collection of the past, where it found

its place next to modernism as well as within modernism, even

to an extent where the division between the avant-garde and

modernism becomes invisible.(10) It is aimed at the fact that

the world can not be changed with works of art, however shocking

and exciting these works of art may be. And at this the arm

is critically waved over two types of 'political' art, which

are the most profiled at this moment in time. The first type

is art, which serves the community and its needs to create

self-images and images for others (today this is usually called

identity and it belongs alongside the 'Indian', 'post-colonial'

and other necessary for the construction of one's identity

likeness) as well as all of that that could be seen at the

Manifesta and in ŠKUC: sentimental Hollywood mourning image

or the self-image of Bosnia during the war and after it, which

supposedly represents engaged art. The other type of 'political'

art is that, which literally or in a figurative meaning of

the word acts as a wholesome designer of barricades and weapons,

with which the anti-capitalist movement from Seattle to Quebec

is attacking global capitalism.

This type is romantically pathetic, such as for example the

Democracy exhibition, set up last year at the Royal College

of Art in London, which the Art Monthly critic JJ Charlesworth

recognised as an artistic parallel to the Labour day demonstrations

and the soiling of Churchill's statue, and already with the

first sentence rejected it as cheap fashion: 'Social conscience

and political engagement in art is back in the mainstream.'(11)

Thus he brings the critical analysis to the conclusion, that

with this mainstream politisation of art we have only gained

a therapeutic self-expression of people within a society with

no alternative and artistic autonomy without any art.

Of course, this is exactly what the historical avant-garde

claimed to hold true for the concept of autonomy and the concept

of society. That, which was politically subversive, for certain

was not serving the artistic ideals (which are not from this

world) neither the transition into a social movement which

would serve the correct political ideals.

Today's art is not subversive? Art can not even be subversive.

Today's avant-garde is not aesthetically digestible? The avant-garde

can not at all be aesthetically digestible. Political subversion

is always aesthetically indigestible and socially useless.

Whoever is looking for it in the mainstream, will never find

it.

1. Miklavž Prosenc, Die Dadaisten in Zürich,

H. Bouvier u. CO. Verlag, Bonn, 1967, pp. 5-6.

2. Georges Hugnet, L'aventure Dada (1916-1922), Paris,

1957, p. 7 of the Tzara foreword to the book: 'Dada a essayé

non pas autant de détrouire l'art et littérature, que l'idée

qu'on s'en était faite'; Quoted by Miklavž Prosenc, p. 66.

3. This is also described in my study 'Jedermann sein eigner

Fussball', Estetika in poslanstvo, Znanstveno in publicistično

središče, Ljubljana, 1994, pp. 75 - 79.

4. Jan Mukarovski, Struktura pesničkog jezika (The structure

of poetry language), Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva,

Belgrade, 1985 (especially the studies on the aesthetics of

language and poetic language), and Jan Mukarovski, Struktura,

funkcija, znak, vrednost (Structure, function, sign,

value), Nolit, Belgrade, 1987 (especially 'Pesničko delo

kao skup vrednosti' ('A work of poetry as a total of values'),

pp. 238-244).

5. Theodor Lipps, 'O formi estetske apercepcije' (On the form

of aesthetic aperception), Filozofija na maturi 1/2-2000,

pp. 14-19; 'What we see, is thus taken exactly as a double

subordination and not merely a single, on each and every occasion.

Also the relation between the elements and the whole is already

a subordination

and

the whole is once more subordinated

to one single element and within it the remaining elements

become factors. I normally define this double subordination

as monarchic' subordination.' (1902).

6. Georg Wilhelm Frierich Hegel, Basic lines of legal philosophy

or Natural law and civics in a draft outline, &262;

quoted from the Slovene translation in Karl Marx - Friedrich

Engels, Collected works I. 'The critic of Hegel's state

law' (manuscript from 1843), Cankarjeva Založba, Ljubljana,

1969, p. 59.

7. Scott Lash, Sociology of Postmodernism (Slovene

translation), Znanstveno in publicistično središče, Ljubljana,

1993, p. 16.

8. Ibid., p. 22.

9. This is also why ustvarjanje antipolitike (creating

anti-politics) by Tonči Kuzmanić can also be read as a

criticism of the 'social movements' in the 1960's and 'civil

rights movements' of the 1980's, even though it directly speaks

only about what 'was pushed out if not completely destroyed

by the society and social sciences with their intensive, almost

colonial brutal development, i.e. from the standing point

of the politics and political' (Tonči Kuzmanić, Ustvarjanje

antipolitike, Znanstveno in publicistično središče, Ljubljana,

1996, p. 9).

10. That is the review of 20th Century art, which was set

as an installation for the opening of Tate Modern in London

last year: the entire 20th Century is compromised and synthesised

as an entity, from which the avant-garde as a special entity

or at least an autonomous part can not be seen any more.

11. JJ Charlesworth, 'Mayday! May Day!', Art Monthly,

London, May 2000 No. 236, p. 13.

Lev Kreft: philospher and sociologist, lecturer of aesthetics

at the Faculty of Arts in Ljubljana, President of the Slovenian

Society of Aesthetics, President of the Peace Institute Board,

Ljubljana.

|