Stripburger št.

MILIONS OF MEGAPIXELS OF SUBJECTIVE RESOLUTION

Text:

Jakob Klemenčič, Sketches: Peter Kuper

The selections, bound in books, (complete replicas are rare) by the respected artists, appear from time to time in bookstores. But it seems that the comic artists and specialized illustrators have taken over the travel themes. The old and the new hobby, 'sketch booking' and 'journaling' (besides the artistic and verbal documentation, they also include pasted materials that are thin enough to be included) are booming in the West nowadays, whereas in the francophone area, the publishing of travel sketches is becoming a true trend. Different variants to the theme, from alternative, often quite new-agey showings of various exotic places, to systematic showings of French regions find their place in catalogues of many publishers. So it's hardly a surprise to see the »Biennale du carnet de voyage«, a festival/meeting of travelers/artists in Clermont-Ferrand with workshops, discussions and meetings, open its doors for six consecutive years.

There's also no surprise that the artists, that have had their travel sketches published, are in majority those comic artists, who deal with this thematic even in their comic strips. In Loustal's series, 'Carnet de voyages' (the 5th book is out since January), we encounter exactly the same visual world and impressions, as in his comic stories: wide horizons, clear, intensive colors, exotic fauna and hotel lethargy. If it can be said for Loustal that many of the compositions and postures can be repeatedly found by trained eye in (numerous) illustrations, silkscreen prints and paintings, this cannot be said for books containing 'sketches from the road'. The effect is a direct opposite: the published 'sketch' is the end product, made in a comfort of home atelier with a generous help of the photo material. Even Jacques Ferrandez, the artist who spurted out a whole series of a drawn and painted documentaries from the Muslim world, inspired by the success of the 'Carnets d'Orient' series, in which he'd used 'documentary' watercolors to complement his story. Namely, the main character, a Frenchman living in Algiers, is a painter. The last of the series is titled »Les trams de Sarajevo«. Among the more direct reports are – also because of their black and white style, but mostly because of a major role of the text – the ones made by Badouin: documentaries from Chile (published independently by L'Association) and Alexandria (in anthology of four stories/documentaries, also by L'Association). Even tighter web of spontaneous sketches and relatively large blocks of text can be found in Blutch's album called »Lettre Americaine« (Cornelius); a comparison with the book of the most famous siamese twins in comics, Dupuy and Berberian, who dedicated one of their sketch collections (besides Lissabon and Tangier) to New York, is a rather interesting one. Their text is reduced to minimum (they only mention the name of the place), which can be attributed to their sense of aesthetics and non-problematic themes (not to mention their love towards line art, created with a brush). In that way, they resemble Loustal, but they also use an emotionally much lighter register (although graphically darker). Christophe Blain uses a much more relaxed artistic approach. His sketch collection from Latvia, his last publication of this kind, was made (like some of the aforementioned) on a sponsored travel in a framework of the French international cultural projects.

A special drainage of orthodox, more or less on location produced sketches are publications, in which artists/artists take a step further from merely colorizing the sights with their own artistic styles. Jano's collections of full-paged watercolors of distinctive locations in sub-Saharan Africa and Rio de Janeiro certainly fall into this category. In these collections, Jano documented the architecture and vegetation with extreme precision and populated them with anthropomorphic rodents and other animals, all in his distinctive manner and, of course, authentic costumography. These kinds of enterprises are usually done in pairs of artists and writers. Jano teamed with Dodo and Ben Radis in his work about India and Nicolas de Crecy collaborated with Raphael Meltz for his 'imaginary' Lisbon.

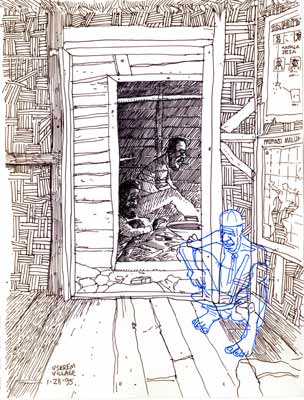

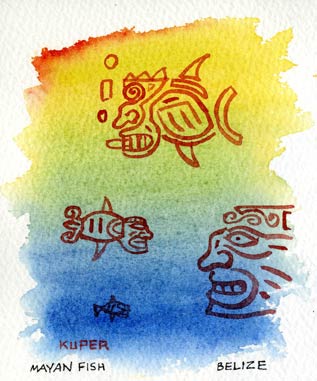

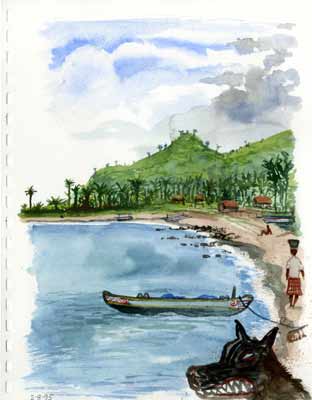

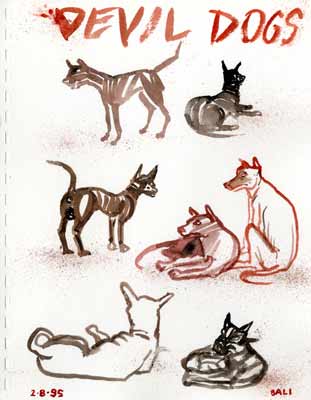

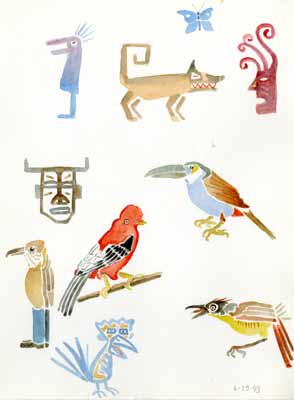

On the other side of the Atlantic, the trend of publishing extensive travel documentaries is a much lesser one – as if they were trying to say, that drawing pretty pictures on a trip is not enough to get published. European publications may be compared to Kuper's »ComicTrips«, maybe because of its (partial) four color print and the fact that it's concentrated on traveling. But it's above the European publication in view of his diversity, on-the-spot-drawing and his trademark collage. In fact, if we used a worn out phrase, its only flaw would be its modest extent. Kuper redeems himself by publishing a CD containing a huge collection of pictures of the terrain; but the computer screen is hardly suitable place for artistic material that was made on paper and bound in books and sketchbooks. Artistically less colorful than that of Kuper, is »Get me a Table without Flies, Harry« by Bill Griffith, but very similar in its satirically spiced viewpoint (although the backgrounds of spiral bindings can be quite annoying). There's always a lot of material for satire and absurd, because Griffith travels (unlike backpacker Kuper) through tourist resorts and European cultural capitols only. In spite of everything, it seems the planned series (the current book is number one of the series) won't be published. Another traveler through cultural Europe is Craig Thompson (he also visited Morocco), who put together his own »Carnets de Voyage« (Top Shelf), a large publication, full of beautiful drawings with which he wanted (hence the title) to turn back to the tradition of francophone sketchbook publications. But as the old truth says, the artist in the end always depicts himself. Thompson, however, seems to go too far in this direction (considering the genre).

In Northern American artists, the travel materials often appears as a part of published sketchbooks with »miscellaneous« contents, like Ware, Crumb and Collier (and on this side of the Atlantic, Trondheim and Sfar, for example). It is as if they wanted to remove the exotics from the pedestal of the privileged, sketch-worthy motifs and show, that even hometown streets and interiors and people can be viewed with curious and watchful eyes of a tourist. But it's more difficult – as Matt Madden wrote in his introduction to »The Annotated Sketchbook from a Journey around the Atlantic Nations«, a photocopied mini-edition with travel theme: »It's always (somewhat) easier to make sketches and gather notes while you're traveling, It's so much harder to document everyday life – there's no beginning and no end, and the scope of what you can see, draw or describe is definitely bigger...« The author of these lines would like to point out another thing: when traveling, among complete strangers, it's very easy to pull out the sketchpad and reveal one's artistic knowledge... or artistic ignorance.