Five Steps to Font Freedom

Monday, May 1, 2006, 03:02 PM - Beautiful Code, Copyfight

Think about these scenarios: You don't need to own a font to read a book set in Goudy. You don't need to own Futura to watch a Wes Anderson film. You don't need to own Times to read the Times. You don't need to own any fonts to watch television. Why not? Because that would be insane. And yet this same logic doesn't apply on the internet. Online, a person needs to own a fully licensed version of a font in order to view it in a web browser. You are reading Arial right now. That's right, Arial. Why? Because everybody on Earth has a licensed version of Arial on their computer. The great democracy of the internet has failed to produce typography any better than the least common denominator of system fonts. As a designer, I hope you are outraged and offended. So what can you do about it?

link

via

Wireless Freedom

Wednesday, April 19, 2006, 10:16 PM - Apt-get Install

OpenWrt is a Linux distribution for wireless routers. Instead of trying to cram every possible feature into one firmware, OpenWrt provides only a minimal firmware with support for add-on packages. For users this means the ability to custom tune features, removing unwanted packages to make room for other packages and for developers this means being able to focus on packages without having to test and release an entire firmware.

Link to site

Link to docs

This Essay Breaks the Law

Friday, March 31, 2006, 07:57 PM - Copyfight

By MICHAEL CRICHTON Published in The New York Times, March 19, 2006

* The Earth revolves around the Sun.

* The speed of light is a constant.

* Apples fall to earth because of gravity.

* Elevated blood sugar is linked to diabetes.

* Elevated uric acid is linked to gout.

* Elevated homocysteine is linked to heart disease.

* Elevated homocysteine is linked to B-12 deficiency, so doctors should test homocysteine levels to see whether the patient needs vitamins.

ACTUALLY, I can't make that last statement. A corporation has patented that fact, and demands a royalty for its use. Anyone who makes the fact public and encourages doctors to test for the condition and treat it can be sued for royalty fees. Any doctor who reads a patient's test results and even thinks of vitamin deficiency infringes the patent. A federal circuit court held that mere thinking violates the patent.

Read the rest of the article

Also: Over 5000 nanomedicine/nanotech patents have now been granted, and the patent land grab continues unabated.

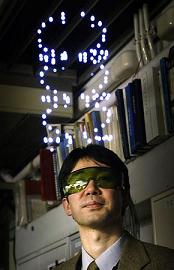

projecting 3D (like you just don't care)

Monday, March 6, 2006, 12:57 PM - Beautiful Code, Games

The National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) has built a system that projects 3D images in less that it takes to say 'hollogram'. The device projevts "real 3D images" which consist of dot arrays in space where there is nothing but air.

The National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) has built a system that projects 3D images in less that it takes to say 'hollogram'. The device projevts "real 3D images" which consist of dot arrays in space where there is nothing but air.

"Until now, projected three-dimensional imagery has been artificial; optical illusions that appear 3D due to the parallax difference between the eyes of the observer. Prolonged viewing of this conventional sort of 3D imagery can cause physical discomfort. The newly developed device, however, creates real 3D images by using laser light, which is focused through a lens at points in space above the device, to create plasma emissions from the nitrogen and oxygen in the air at the point of focus. Because plasma emission continues for a short period of time, the device is able to create 3D images by moving the point of focus."

link to the project

via dottocomu

the problem with the turing test

Friday, March 3, 2006, 04:32 PM - Theory, Robots

In The New Atlantis, Mark Halpern points out a bug in Turing's test: humans don't judge the intelligence of other humans by their response to questions but by their appearence.

In the October 1950 issue of the British quarterly Mind, Alan Turing published a 28-page paper titled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” It was recognized almost instantly as a landmark. In 1956, less than six years after its publication in a small periodical read almost exclusively by academic philosophers, it was reprinted in The World of Mathematics, an anthology of writings on the classic problems and themes of mathematics and logic, most of them written by the greatest mathematicians and logicians of all time. (In an act that presaged much of the confusion that followed regarding what Turing really said, James Newman, editor of the anthology, silently re-titled the paper “Can a Machine Think?”) Since then, it has become one of the most reprinted, cited, quoted, misquoted, paraphrased, alluded to, and generally referenced philosophical papers ever published. It has influenced a wide range of intellectual disciplines—artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, epistemology, philosophy of mind—and helped shape public understanding, such as it is, of the limits and possibilities of non-human, man-made, artificial “intelligence.”

Turing’s paper claimed that suitably programmed digital computers would be generally accepted as thinking by around the year 2000, achieving that status by successfully responding to human questions in a human-like way. In preparing his readers to accept this idea, he explained what a digital computer is, presenting it as a special case of the “discrete state machine”; he offered a capsule explanation of what “programming” such a machine means; and he refuted—at least to his own satisfaction—nine arguments against his thesis that such a machine could be said to think. (All this groundwork was needed in 1950, when few people had even heard of computers.) But these sections of his paper are not what has made it so historically significant. The part that has seized our imagination, to the point where thousands who have never seen the paper nevertheless clearly remember it, is Turing’s proposed test for determining whether a computer is thinking—an experiment he calls the Imitation Game, but which is now known as the Turing Test.

READ the rest of the article by Mark Halpern.

via robots.net

humanoid from here

Word files in the command line

Wednesday, March 1, 2006, 02:33 PM - Apt-get Install

Antiword is a nifty application that can convert Word documents to plain text, PostScript, and PDF. According to the developer, conversion to DocBook XML is still experimental and doesn't always work well.

Antiword is very flexible. It can read and convert files created with Word versions 2.0 to 2003, and you can run it on multiple operating systems, including Linux, Mac OS X, RISC OS, FreeBSD, and OpenVMS. On top of that, you can set the paper size for documents converted to PostScript or PDF, include any text that was removed from the file (but which Word notoriously keeps a record of), and display any hidden text.

For the most part, you'll just want to view a Word document. To do that, you just have to type the following command:

antiword file.doc

The Word document will be converted to text and printed to the screen. If you're running Antiword in a terminal window, you'll have to scroll up to view the full text of the document. To get around this, you can pipe the output from Antiword to the less utility, which will allow you to scroll through the document page by page from the top:

antiword file.doc | less

Antiword

article in Linux.com

3D textures tutorial

Monday, February 27, 2006, 03:28 PM - Games

Derek Lea explains how to add textured surfaces and tactile elements to 3D renderings in Photoshop. The unique results will reveal a combination of the depth provided by 3D and the painterly freedom of working in 2D.

3D texturizing tutorial

also perfect faces and CG lighting.

via blogyourmind

Back Next