qué talento para el mal

Wednesday, February 7, 2007, 05:56 PM - Copyfight, Media

Steve Job's thoughts on music. Music meaning DRM:

Some have argued that once a consumer purchases a body of music from one of the proprietary music stores, they are forever locked into only using music players from that one company. Or, if they buy a specific player, they are locked into buying music only from that company’s music store. Is this true? Let’s look at the data for iPods and the iTunes store – they are the industry’s most popular products and we have accurate data for them. Through the end of 2006, customers purchased a total of 90 million iPods and 2 billion songs from the iTunes store. On average, that’s 22 songs purchased from the iTunes store for each iPod ever sold.I'm impressed. And so is Jon Lech Johansen.

Today’s most popular iPod holds 1000 songs, and research tells us that the average iPod is nearly full. This means that only 22 out of 1000 songs, or under 3% of the music on the average iPod, is purchased from the iTunes store and protected with a DRM. The remaining 97% of the music is unprotected and playable on any player that can play the open formats. Its hard to believe that just 3% of the music on the average iPod is enough to lock users into buying only iPods in the future. And since 97% of the music on the average iPod was not purchased from the iTunes store, iPod users are clearly not locked into the iTunes store to acquire their music.

MORE: You say you want a revolution | Norway responds to Jobs' open DRM letter

EXTRA: Apple vs Apple is over

On Plagiarism

Monday, January 29, 2007, 12:09 AM - Copyfight

Richard A. Posner, The Atlantic Monthly; April 2002

Recently two popular historians were discovered to have lifted passages from other historians' books. They identified the sources in footnotes, but they failed to place quotation marks around the purloined passages. Both historians were quickly buried under an avalanche of criticism. The scandal will soon be forgotten, but it leaves in its wake the questions What is "plagiarism"? and Why is it reprobated? These are important questions. The label "plagiarist" can ruin a writer, destroy a scholarly career, blast a politician's chances for election, and cause the expulsion of a student from a college or university. New computer search programs, though they may in the long run deter plagiarism, will in the short run lead to the discovery of more cases of it.

We must distinguish in the first place between a plagiarist and a copyright infringer. They are both copycats, but the latter is trying to appropriate revenues generated by property that belongs to someone else—namely, the holder of the copyright on the work that the infringer has copied. A pirated edition of a current best seller is a good example of copyright infringement. There is no copyright infringement, however, if the "stolen" intellectual property is in the public domain (in which case it is not property at all), or if the purpose is not appropriation of the copyright holder's revenue. The doctrine of "fair use" permits brief passages from a book to be quoted in a book review or a critical essay; and the parodist of a copyrighted work is permitted to copy as much of that work as is necessary to enable readers to recognize the new work as a parody. A writer may, for that matter, quote a passage from another writer just to liven up the narrative; but to do so without quotation marks—to pass off another writer's writing as one's own—is more like fraud than like fair use.

"Plagiarism," in the broadest sense of this ambiguous term, is simply unacknowledged copying, whether of copyrighted or uncopyrighted work. (Indeed, it might be of uncopyrightable work—for example, of an idea.) If I reprint Hamlet under my own name, I am a plagiarist but not an infringer. Shakespeare himself was a formidable plagiarist in the broad sense in which I'm using the word. The famous description in Antony and Cleopatra of Cleopatra on her royal barge is taken almost verbatim from a translation of Plutarch's life of Mark Antony: "on either side of her, pretty, fair boys apparelled as painters do set forth the god Cupid, with little fans in their hands, with which they fanned wind upon her" becomes "on each side her / Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids, / With divers-colour'd fans, whose wind did seem / To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool." (Notice how Shakespeare improved upon the original.) In The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot "stole" the famous opening of Shakespeare's barge passage, "The barge she sat in, like a burnish'd throne, / Burn'd on the water" becoming "The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne, / Glowed on the marble."

Mention of Shakespeare brings to mind that West Side Story is just one of the links in a chain of plagiarisms that began with Ovid's Pyramus and Thisbe and continued with the forgotten Arthur Brooke's The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, which was plundered heavily by Shakespeare. Milton in Paradise Lost plagiarized Genesis, as did Thomas Mann in Joseph and His Brothers. Examples are not limited to writing. One from painting is Edouard Manet, whose works from the 1860s "quote" extensively from Raphael, Titian, Velásquez, Rembrandt, and others, of course without express acknowledgment.

If these are examples of plagiarism, then we want more plagiarism. They show that not all unacknowledged copying is "plagiarism" in the pejorative sense. Although there is no formal acknowledgment of copying in my examples, neither is there any likelihood of deception. And the copier has added value to the original—this is not slavish copying. Plagiarism is also innocent when no value is attached to originality; so judges, who try to conceal originality and pretend that their decisions are foreordained, "steal" freely from one another without attribution or any ill will.

But all that can be said in defense of a writer who, merely to spice up his work, incorporates passages from another writer without acknowledgment is that the readability of his work might be impaired if he had to interrupt a fast-paced narrative to confess that "a predecessor of mine, ___, has said what I want to say next better than I can, so rather than paraphrase him, I give you the following passage, indented and in quotation marks, from his book ___." And not even that much can be said in defense of the writer who plagiarizes out of sheer laziness or forgetfulness, the latter being the standard defense when one is confronted with proof of one's plagiarism.

Because a footnote does not signal verbatim incorporation of material from the source footnoted, all that can be said in defense of the historians with whom I began is that they made it easier for their plagiarism to be discovered. This is relevant to how severely they should be criticized, because one of the reasons academic plagiarism is so strongly reprobated is that it is normally very difficult to detect. (In contrast, Eliot and Manet wanted their audience to recognize their borrowings.) This is true of the student's plagiarized term paper, and to a lesser extent of the professor's plagiarized scholarly article. These are particularly grave forms of fraud, because they may lead the reader to take steps, such as giving the student a good grade or voting to promote the professor, that he would not take if he knew the truth. But readers of popular histories are not professional historians, and most don't care a straw how original the historian is. The public wants a good read, a good show, and the fact that a book or a play may be the work of many hands—as, in truth, most art and entertainment are—is of no consequence to it. The harm is not to the reader but to those writers whose work does not glitter with stolen gold.

On Plagiarism

inside eBay's Innovation Machine

Thursday, January 4, 2007, 04:39 PM - Beautiful Code, Media

Business is steady on an early december afternoon at the iSold It consignment store on Skeet Club Road in High Point, N.C., as customers drop off items to be sold on eBay. Bikes, electronics, power tools --a steady flow of stuff, forming a tributary to the nearly $50 billion flood of goods and services that will be sold on the giant online marketplace in 2006.

iSold It LLC, with almost 200 outlets from coast to coast, has become one of the largest sellers on eBay Inc. by making it simple for anyone to move merchandise across the sprawling auction site. Simple for the folks consigning the stuff, that is -they just fill out a quick form, then go home to watch their online auction and wait for a check- but a fair amount of work for iSold It's employees, who must check the items in, list them in the most advantageous areas on eBay, keep track of bidding and sales, and follow through with shipping and payment.

Multiply that by the 50,000 different auctions iSold It manages in a typical month -about 15,000 at any given moment, closer to 18,000 during the December holiday rush- and, well, "it gets very complex," says Dave Crocker, senior vice president of business development at the privately held Monrovia, Calif., company. To deal with that complexity, iSold It is switching from internally developed software to a more sophisticated application from a Salt Lake City firm called Infopia Inc., which links directly to various eBay sites and handles pricing, listing and other key tasks more efficiently.

Infopia is not just another software vendor. It's part of a growing community of some 40,000 independent developers, all building products using eBay's own application programming interfaces, or APIs -the connection points that let a program share data and respond to requests from other software. These applications are tailor-made to work seamlessly with eBay's core computing platform. eBay provides its APIs to the developers for free; its cost is limited to maintaining the code and providing some support resources for the developers.

The payoff: a network of companies creating applications that help make eBay work better, grow faster and reach a broader customer base. (eBay's other business units, Skype and PayPal, also have open APIs and developer programs.) eBay says that software created by its developer network—there are more than 3,000 actively used applications, including a configurator that allows high-volume sellers to list items more efficiently, and a program that notifies buyers of auction status via mobile phone -plays a role in 25 percent of listings on the U.S. eBay site. The company has about 105 million listed items at any given time; roughly half of its sales come from within the United States.

Sharing APIs is common practice for software companies, but eBay, along with its fellow online-retail pioneer, Amazon.com, is breaking new ground in its industry by establishing a large community of outside developers. And the implications of this strategy go much further than the world of auctions and electronic storefronts. "It's about allowing people outside your company to write services that communicate with you-—it could be companies in your supply chain, sharing information about inventories or billing," says Adam Trachtenberg, senior manager of platform evangelism at eBay (i.e., the guy responsible for the care and feeding of the developer program).

"In the next few years you will see more and more companies with third-party developer networks, even companies you might not think of as likely candidates," adds Zeus Kerravala, senior vice president of enterprise research at Yankee Group. That could mean companies in far more traditional businesses than eBay, including manufacturers, he says. "These days, executives are telling me 'we're more like a software company than a hardware company'—and I say, then act like one. The long-term winners and losers in markets are determined by ecosystems around them, and developer networks fit that model. Developer communities allow companies to do things over the Internet with resources they don't have themselves," he says. Companies can't just flip a switch and join the game, though, says Daniel Sholler, a research vice president at Gartner Inc. They may need to first embrace the design model of service-oriented architecture, which hides the underlying complexity of a system from users, and allows components of an IT infrastructure to be reused and recombined to support particular processes instead of dedicated tasks. "This is part of the maturation of the Web, the trend toward service-enabling all kinds of systems and sharing information more freely," Sholler says.

Companies such as Infopia are now creating mash-ups—applications built around APIs from eBay and other firms such as SalesForce.com Inc. and FedEx Corp.—that extend the relationship between different companies and their customers. The mash-ups loosely join unrelated entities, portending a new level of interactivity between companies and customers of all kinds. "This is what Web 2.0 does for business," says Infopia CEO Bjorn Espenes. "Everyone can pick and share information in different ways that are much more automated."

Keep reading Inside eBay by Edward Cone at Cio insight!

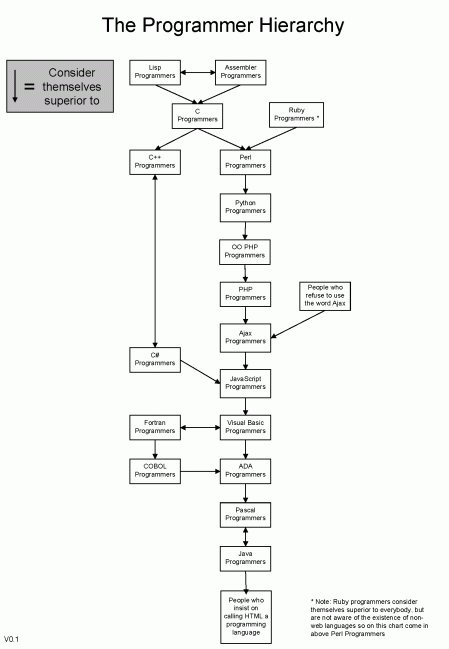

The programmer hierarchy

a patents christmas tale

Tuesday, December 26, 2006, 03:25 PM - Copyfight

Scrooge and intellectual property rights

by Joseph E Stiglitz, professor At Christmas, we traditionally retell Dickens's story of Scrooge, who cared more for money than for his fellow human beings. What would we think of a Scrooge who could cure diseases that blighted thousands of people's lives but did not do so? Clearly, we would be horrified. But this has increasingly been happening in the name of economics, under the innocent sounding guise of "intellectual property rights."

Intellectual property differs from other property—restricting its use is inefficient as it costs nothing for another person to use it. Thomas Jefferson, America's third president, put it more poetically than modern economists (who refer to "zero marginal costs" and "non-rivalrous consumption") when he said that knowledge is like a candle, when one candle lights another it does not diminish from the light of the first. Using knowledge to help someone does not prevent that knowledge from helping others. Intellectual property rights, however, enable one person or company to have exclusive control of the use of a particular piece of knowledge, thereby creating monopoly power. Monopolies distort the economy. Restricting the use of medical knowledge not only affects economic efficiency, but also life itself.

We tolerate such restrictions in the belief that they might spur innovation, balancing costs against benefits. But the costs of restrictions can outweigh the benefits. It is hard to see how the patent issued by the US government for the healing properties of turmeric, which had been known for hundreds of years, stimulated research. Had the patent been enforced in India, poor people who wanted to use this compound would have had to pay royalties to the United States.

In 1995 the Uruguay round trade negotiations concluded in the establishment of the World Trade Organization, which imposed US style intellectual property rights around the world. These rights were intended to reduce access to generic medicines and they succeeded. As generic medicines cost a fraction of their brand name counterparts, billions could no longer afford the drugs they needed. For example, a year's treatment with a generic cocktail of AIDS drugs might cost $130 (£65; 170) compared with $10 000 for the brand name version.1 Billions of people living on $2-3 a day cannot afford $10 000, though they might be able to scrape together enough for the generic drugs. And matters are getting worse. New drug regimens recommended by the World Health Organization and second line defences that need to be used as resistance to standard treatments develops can cost much more.

Developing countries paid a high price for this agreement. But what have they received in return? Drug companies spend more on advertising and marketing than on research, more on research on lifestyle drugs than on life saving drugs, and almost nothing on diseases that affect developing countries only. This is not surprising. Poor people cannot afford drugs, and drug companies make investments that yield the highest returns. The chief executive of Novartis, a drug company with a history of social responsibility, said "We have no model which would [meet] the need for new drugs in a sustainable way ... You can't expect for-profit organizations to do this on a large scale."2

Research needs money, but the current system results in limited funds being spent in the wrong way. For instance, the human genome project decoded the human genome within the target timeframe, but a few scientists managed to beat the project so they could patent genes related to breast cancer. The social value of gaining this knowledge slightly earlier was small, but the cost was enormous. Consequently the cost of testing for breast cancer vulnerability genes is high. In countries with no national health service many women with these genes will fail to be tested. In counties where governments will pay for these tests less money will be available for other public health needs.

A medical prize fund provides an alternative. Such a fund would give large rewards for cures or vaccines for diseases like malaria that affect millions, and smaller rewards for drugs that are similar to existing ones, with perhaps slightly different side effects. The intellectual property would be available to generic drug companies. The power of competitive markets would ensure a wide distribution at the lowest possible price, unlike the current system, which uses monopoly power, with its high prices and limited usage.

The prizes could be funded by governments in advanced industrial countries. For diseases that affect the developed world, governments are already paying as part of the health care they provide for their citizens. For diseases that affect developing countries, the funding could be part of development assistance. Money spent in this way might do as much to improve the wellbeing of people in the developing world—and even their productivity—as any other that they are given.

The medical prize fund could be one of several ways to promote innovation in crucial diseases. The most important ideas that emerge from basic science have never been protected by patents and never should be. Most researchers are motivated by the desire to enhance understanding and help humankind. Of course money is needed, and governments must continue to provide money through research grants along with support for government research laboratories and research universities. The patent system would continue to play a part for applications for which no one offers a prize . The prize fund should complement these other methods of funding; it at least holds the promise that in the future more money will be spent on research than on advertising and marketing of drugs, and that research concentrates on diseases that matter. Importantly, the medical prize fund would ensure that we make the best possible use of whatever knowledge we acquire, rather than hoarding it and limiting usage to those who can afford it, as Scrooge might have done. It is a thought we should keep in mind this Christmas.

1 Columbia University, New York, NY 10025, USA

note. Joseph E Stiglitz was chief economist of the World Bank from 1997 to 2000 and a member and then chairman of President Clinton's Council of Economic Advisers from 1993 to 1997. He won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2001.

Read the article in the British Medical Journal where it was originally published.

Hoping to Be a Model, I.B.M. goes open patent

Tuesday, September 26, 2006, 05:59 PM - Copyfight

"The larger picture here is that intellectual property is the crucial capital in a global knowledge economy," -said Samuel J. Palmisano, I.B.M.'s chief executive. "If you need a dozen lawyers involved every time you want to do something, it's going to be a huge barrier. We need to make sure that intellectual property is not used as a barrier to growth in the future."

Read the whole article in the NYTimes

artillería: napster & the concert value

Monday, August 28, 2006, 09:56 PM - Copyfight

In a study about ticket prices for concerts, the Princeton economist Alan B. Krueger found that between 1983 and 2003, a period in which MTV, Napster, the iPod and other technologies extended the reach of top acts, the share of concert revenue taken by the top 5 percent of artists increased to 84 percent, from 62 percent.

As read in A Big Star May Not a Profitable Movie Make, NYTimes

Back Next