All Rights Reserved: a history of American copyright law by Jeff Siegel

Tuesday, July 18, 2006, 05:06 PM - Copyfight

<i>To every cow her calf, and to every book its copy.” -- Irish King Dermott, 6th c. C.E., in his decision Finnian v. Columba (The “Abbot's Psalter” case). Probably apocryphal.</i>

it's part of American law, and among other things the philosophical and legal foundation for "work for hire," the idea that an author can be hired by an institution, paid a flat fee, and rescind all rights to the work they've created, as if the author were never involved in the first place; the publisher, not as agent of the author, but as the author. The vast majority of cultural and intellectual work is created within a work for hire arrangement, the creator ceding her work to the institution that manufactures, markets, distributes, and sells it (and it's the work, the expression of the idea, that's covered in copyright, not the idea itself). There's much talk from spokespeople for the various trade groups involved in bringing litigation on copyright matters (RIAA, MPAA, BSA for software companies, etc.) that copyright infringement harms most the authors of the work, that it takes money out of their pockets, undoing the incentive to create more work for the public good. But due to these work-for-hire arrangements, it's the opposite that's true; there is no significant correlation between a corporate entity controlling a copyright on a work and the creator of that work making money from its sale. Nowhere is this clearer than in the music business. By now you've heard story after story of artists getting screwed by their labels. The minuscule royalties and recoupable costs and so forth are only a manifestation of the real issue: the constant downward pressure of a big record label onto the livelihood of its only real asset, the recording artist who creates the product that generates their profit. As a generalization, there are few worse positions to be in in the commercial arts than major-label recording artist. Book publishing works on a fundamentally similar model, but rarely do publishers make their writers recoup marketing costs or advances; film and broadcasting, especially at big-money levels, are fully unionized, and everyone involved makes a set wage. So how do record labels get away with making tidy profits on ubiquitous songs, while the artists rarely see a dime and usually end up in debt?

Read All Rights Reserved in Stylus Magazine.

via

M$ forgotten monopoly

Tuesday, July 11, 2006, 09:37 AM - Copyfight

Hakon Wium Lie, Opera's CEO & CSS creator on font politics:

Microsoft's font monopoly is due to the "Core fonts for the Web" program it launched in 1996. About 10 font families--including familiar names like Arial, Georgia, Verdana and Times New Roman--were made available "for free to the Web community, on all platforms" as Microsoft told the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) at the time. The fonts have served us well. They've improved both aesthetics and interoperability on the Web, and they look good in a wide range of sizes. Unfortunately, Microsoft decided to close the project in 2002. The fonts are still available for anyone to use, but not to change. It is illegal to add support for more non-Western scripts. The time has come to break the Microsoft monopoly on fonts. This is easier than it sounds. There are thousands of font families on the Web--I call them Web fonts--that are freely available for anyone to use. One such font family, for example, is Goodfish, an elegant serifed font designed by Ray Larabie in 2000. It comes in four variants (regular, italic, bold, bold italic), which are encoded as four TrueType files. When zipped, the files take up about 100k of memory. That's about the same file size as a small photograph.

keep reading Microsoft's forgotten monopoly

ALSO HERE: 5 steps to font freedom

Pay a little now, pay a lot later

Tuesday, July 11, 2006, 09:30 AM - Copyfight

Choosing freedom or bondage isn't very important for a typical home computer user. Most people only use the software that comes bundled with their computer, and perhaps the occasional shareware game. Basically, they don't invest much in their setup beyond the original hardware purchase. Replace their PC with a Mac or a Linux box and they'd probably forget the difference after a day or so. This is not the case, though, with businesses who dedicate significant portions of their income to IT. It's often prohibitively expensive to alter a company's computing infrastructure once it's been established, so choosing well from the first day is critically important. That is one of the main reasons why I could never recommend a proprietary system to a business owner.

keep reading Pay a little now, pay a lot later, by Kirk Strauser.

Where's My Google PC?

Friday, July 7, 2006, 11:47 AM - Apt-get Install

Paul Boutin talks about Google PC and the OS market in Slate:

Unless you're playing Grand Theft Auto or watching HDTV, your network isn't the slowest part of your setup. It's the consumer-grade Pentium and disk drive on your Dell, and the wimpy home data bus that connects them. Home computers are marketed with slogans like "Ultimate Performance," but the truth is they're engineered to run cool, quiet, and slow compared to commercial servers. Google's Web search is blindingly fast because your requests get handled by a sprawling array of loud, hot, power-hungry server racks that you'd never allow in your house. All your home computer has to do is draw the results of Google's massive data-mining process on its screen- that's the easy part.

Read the article

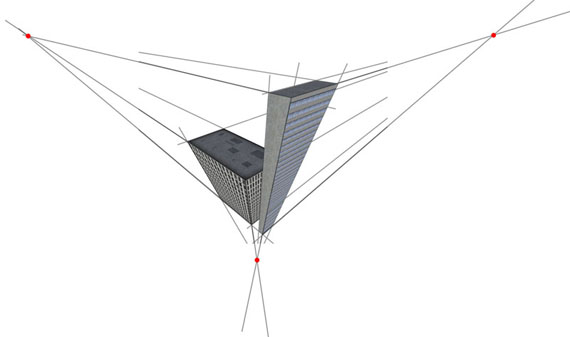

game art: textures, features, perspectives

Friday, June 23, 2006, 12:27 PM - Games, Howto

Gamasutra publishes an excerpt from 3D Game Textures: Create Professional Game Art Using Photoshop(Focal Press, February 2006). Where we read PS though, we might as well say Gimp. Blender and Gimp are very close friends aren't they.

More videogames here

Before there was Linux

Tuesday, May 30, 2006, 03:54 PM - Copyfight

Andy Updegrove on Squaring the Open Source/Open Standards Circle:

"Before there was Linux, before there was open source, there was of course (and still is) an operating system called Unix that was robust, stable and widely admired. It was also available under license to anyone that wanted to use it, and partly for that reason many variants grew up and lost interoperability - and the Unix wars began. Those wars helped Microsoft displace Unix with Windows NT, which steadily gained market share until Linux, a Unix clone, in turn began to supplant NT. Unfortunately, one of the very things that makes Linux powerful also makes it vulnerable to the same type of fragmentation that helped to doom Unix - the open source licenses under which Linux distributions are created and made available.

Happily, there is a remedy to avoid the end that befell Unix, and that remedy is open standards - specifically, the Linux Standards Base (LSB). The LSB is now an ISO/IEC standard, and was created by the Free Standards Group. In a recent interview, the FSG's Executive Director, Jim Zemlin, and CTO, Ian Murdock, creator of Debian GNU/Linux, tell how the FSG works collaboratively with the open source community to support the continued progress of Linux and other key open source software, and ensure that end users do not suffer the same type of lock in that traps licensees of proprietary software products."

Why we all sell code with bugs

Thursday, May 25, 2006, 10:59 PM - Apt-get Install

Eric Sink in The Guardian

The world's six billion people can be divided into two groups: group one, who know why every good software company ships products with known bugs; and group two, who don't. Those in group 1 tend to forget what life was like before our youthful optimism was spoiled by reality. Sometimes we encounter a person in group two, a new hire on the team or a customer, who is shocked that any software company would ship a product before every last bug is fixed.

Every time Microsoft releases a version of Windows, stories are written about how the open bug count is a five-digit number. People in group two find that interesting. But if you are a software developer, you need to get into group one, where I am. Why would an independent software vendor - like SourceGear - release a product with known bugs? There are several reasons:

· We care about quality so deeply that we know how to decide which bugs are acceptable and which ones are not.

· It is better to ship a product with a known quality level than to ship a product full of surprises.

· The alternative is to fix them and risk introducing worse bugs.

Sure. May I add: because every time you fix your own bugs you can sell the product again. Or sell the patches.

Back Next