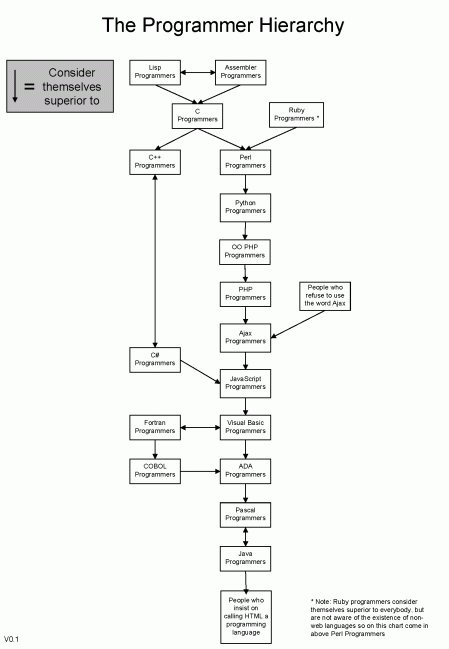

The programmer hierarchy

a patents christmas tale

Tuesday, December 26, 2006, 03:25 PM - Copyfight

Scrooge and intellectual property rights

by Joseph E Stiglitz, professor At Christmas, we traditionally retell Dickens's story of Scrooge, who cared more for money than for his fellow human beings. What would we think of a Scrooge who could cure diseases that blighted thousands of people's lives but did not do so? Clearly, we would be horrified. But this has increasingly been happening in the name of economics, under the innocent sounding guise of "intellectual property rights."

Intellectual property differs from other property—restricting its use is inefficient as it costs nothing for another person to use it. Thomas Jefferson, America's third president, put it more poetically than modern economists (who refer to "zero marginal costs" and "non-rivalrous consumption") when he said that knowledge is like a candle, when one candle lights another it does not diminish from the light of the first. Using knowledge to help someone does not prevent that knowledge from helping others. Intellectual property rights, however, enable one person or company to have exclusive control of the use of a particular piece of knowledge, thereby creating monopoly power. Monopolies distort the economy. Restricting the use of medical knowledge not only affects economic efficiency, but also life itself.

We tolerate such restrictions in the belief that they might spur innovation, balancing costs against benefits. But the costs of restrictions can outweigh the benefits. It is hard to see how the patent issued by the US government for the healing properties of turmeric, which had been known for hundreds of years, stimulated research. Had the patent been enforced in India, poor people who wanted to use this compound would have had to pay royalties to the United States.

In 1995 the Uruguay round trade negotiations concluded in the establishment of the World Trade Organization, which imposed US style intellectual property rights around the world. These rights were intended to reduce access to generic medicines and they succeeded. As generic medicines cost a fraction of their brand name counterparts, billions could no longer afford the drugs they needed. For example, a year's treatment with a generic cocktail of AIDS drugs might cost $130 (£65; 170) compared with $10 000 for the brand name version.1 Billions of people living on $2-3 a day cannot afford $10 000, though they might be able to scrape together enough for the generic drugs. And matters are getting worse. New drug regimens recommended by the World Health Organization and second line defences that need to be used as resistance to standard treatments develops can cost much more.

Developing countries paid a high price for this agreement. But what have they received in return? Drug companies spend more on advertising and marketing than on research, more on research on lifestyle drugs than on life saving drugs, and almost nothing on diseases that affect developing countries only. This is not surprising. Poor people cannot afford drugs, and drug companies make investments that yield the highest returns. The chief executive of Novartis, a drug company with a history of social responsibility, said "We have no model which would [meet] the need for new drugs in a sustainable way ... You can't expect for-profit organizations to do this on a large scale."2

Research needs money, but the current system results in limited funds being spent in the wrong way. For instance, the human genome project decoded the human genome within the target timeframe, but a few scientists managed to beat the project so they could patent genes related to breast cancer. The social value of gaining this knowledge slightly earlier was small, but the cost was enormous. Consequently the cost of testing for breast cancer vulnerability genes is high. In countries with no national health service many women with these genes will fail to be tested. In counties where governments will pay for these tests less money will be available for other public health needs.

A medical prize fund provides an alternative. Such a fund would give large rewards for cures or vaccines for diseases like malaria that affect millions, and smaller rewards for drugs that are similar to existing ones, with perhaps slightly different side effects. The intellectual property would be available to generic drug companies. The power of competitive markets would ensure a wide distribution at the lowest possible price, unlike the current system, which uses monopoly power, with its high prices and limited usage.

The prizes could be funded by governments in advanced industrial countries. For diseases that affect the developed world, governments are already paying as part of the health care they provide for their citizens. For diseases that affect developing countries, the funding could be part of development assistance. Money spent in this way might do as much to improve the wellbeing of people in the developing world—and even their productivity—as any other that they are given.

The medical prize fund could be one of several ways to promote innovation in crucial diseases. The most important ideas that emerge from basic science have never been protected by patents and never should be. Most researchers are motivated by the desire to enhance understanding and help humankind. Of course money is needed, and governments must continue to provide money through research grants along with support for government research laboratories and research universities. The patent system would continue to play a part for applications for which no one offers a prize . The prize fund should complement these other methods of funding; it at least holds the promise that in the future more money will be spent on research than on advertising and marketing of drugs, and that research concentrates on diseases that matter. Importantly, the medical prize fund would ensure that we make the best possible use of whatever knowledge we acquire, rather than hoarding it and limiting usage to those who can afford it, as Scrooge might have done. It is a thought we should keep in mind this Christmas.

1 Columbia University, New York, NY 10025, USA

note. Joseph E Stiglitz was chief economist of the World Bank from 1997 to 2000 and a member and then chairman of President Clinton's Council of Economic Advisers from 1993 to 1997. He won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2001.

Read the article in the British Medical Journal where it was originally published.

Hoping to Be a Model, I.B.M. goes open patent

Tuesday, September 26, 2006, 05:59 PM - Copyfight

"The larger picture here is that intellectual property is the crucial capital in a global knowledge economy," -said Samuel J. Palmisano, I.B.M.'s chief executive. "If you need a dozen lawyers involved every time you want to do something, it's going to be a huge barrier. We need to make sure that intellectual property is not used as a barrier to growth in the future."

Read the whole article in the NYTimes

artillería: napster & the concert value

Monday, August 28, 2006, 09:56 PM - Copyfight

In a study about ticket prices for concerts, the Princeton economist Alan B. Krueger found that between 1983 and 2003, a period in which MTV, Napster, the iPod and other technologies extended the reach of top acts, the share of concert revenue taken by the top 5 percent of artists increased to 84 percent, from 62 percent.

As read in A Big Star May Not a Profitable Movie Make, NYTimes

A closed mind about an open world

Wednesday, August 23, 2006, 09:03 PM - Copyfight

Over the past 15 years, a group of scholars has finally persuaded economists to believe something non-economists find obvious: "behavioural economics" shows that people do not act as economic theory predicts.

However, this is not a vindication of folk wisdom over the pointy-heads. The deviations from "rational behaviour" were not the wonderful cornucopia of humanist motivations you might imagine. There were patterns. We were risk-averse when it came to losses - likely to overestimate chances of loss and underestimate chances of gain, for example. We rely on heuristics to frame problems but cling to them even when they are contradicted by the facts. Some of these patterns are endearing; the supposedly "irrational" concerns for equality that persist in all but Republicans and the economically trained, for example. But most were simply the mapping of cognitive bias. We can take advantage of those biases, as those who sell us expensive and irrational warranties on consumer goods do. Or we can correct for them, like a pilot who is trained to rely on his instruments rather than his faulty perceptions when flying in heavy cloud.

Studying intellectual property and the internet has convinced me that we have another cognitive bias. Call it the openness aversion. We are likely to undervalue the importance, viability and productive power of open systems, open networks and non-proprietary production. Test yourself on the following questions. In each case, it is 1991 and I have removed from you all knowledge of the past 15 years.

Keep Reading A closed mind about an open world by James Boyle in the Finantial Times.

Gracias Ricardo.

Regarding Copyright: Is a Scent Like a Song?

Wednesday, August 2, 2006, 06:12 PM - Copyfight

In its ruling, the court, the Cour de Cassation, denied the petition of a perfume maker, who claimed she deserved to continue receiving royalties from a former employer, even after she had been fired. The court stated, "The fragrance of a perfume, which results from the simple implementation of expertise" does not constitute "the creation of a form of expression able to profit from protection of works of the mind."

To confuse matters, a French court of appeals ruled the opposite last January, determining that a perfume could be a "work of the mind" protected by intellectual property law. It ordered a Belgian company to pay damages to the perfume and cosmetics giant L'Oréal, which sued it for producing counterfeits of best-selling L'Oréal perfumes.

The rulings have the noses and the perfume houses of France twitching nervously. Many "noses" consider the scents they create as important and valuable as paintings or poems.

Read the rest of the article, originally published by the NYTimes.

Journalism without journalists

Wednesday, August 2, 2006, 05:55 PM - Media

On the Internet, everybody is a millenarian. Internet journalism, according to those who produce manifestos on its behalf, represents a world-historical development -not so much because of the expressive power of the new medium as because of its accessibility to producers and consumers. That permits it to break the long-standing choke hold on public information and discussion that the traditional media -usually known, when this argument is made, as "gatekeepers" or "the priesthood"- have supposedly been able to maintain up to now. "Millions of Americans who were once in awe of the punditocracy now realize that anyone can do this stuff -and that many unknowns can do it better than the lords of the profession," Glenn Reynolds, a University of Tennessee law professor who operates one of the leading blogs, Instapundit, writes, typically, in his new book, "An Army of Davids: How Markets and Technology Empower Ordinary People to Beat Big Media, Big Government and Other Goliaths."

keep reading Amateur Journalism in the Newyorker.

Back Next